Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » Deconstructing Free Jazz

Deconstructing Free Jazz

I find myself skeptical of music that forces you to have a certain experience, emotional reaction, or specific constructive arc of experience.

—Vijay Iyer

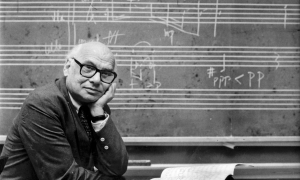

If the terms are not quite interchangeable, Expressionism and free jazz share a common genesis that goes back to the early 20th century with the introduction of the 12-tone chromatic scale, a revolutionary construct that dispensed with a tonal center. Among Expressionism's major luminaries were Anton Webern, Alan Berg and Arnold Schoenberg. In classical music expressionism elevates the subjective realm of human feelings to a paramount position. It embraces atonality as a means of conveying intense psychological states while reflecting the anxieties and upheavals of the era.

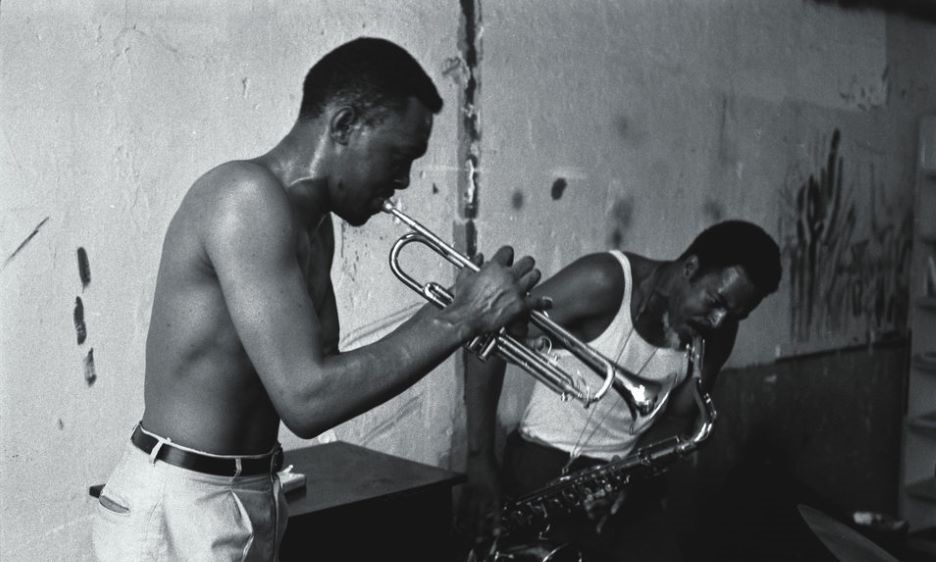

In the late 1940s, Abstract Expressionism takes the art world by surprise. The movement is led by iconoclast Jackson Pollack, who retires his brush in favour of hurling paint at the canvas. With a nod to bebop, the baton is next passed in the 1960s with the explosive arrival of free jazz. In both genres, the aleatoric (chance) is incorporated as a structural device; and with the advent of free jazz, it becomes fashionable to 'compose in real time,' a feat that, by its very nature, blurs the distinction between improvisation and composition.

For the purpose of this essay, I will be using the term free jazz to describe music that emerged in America through the ground breaking work of such Black composers as

Ornette Coleman

saxophone, alto1930 - 2015

John Coltrane

saxophone1926 - 1967

Cecil Taylor

piano1929 - 2018

Sun Ra

piano1914 - 1993

Archie Shepp

saxophone, tenorb.1937

Free jazz, in its broadest strokes, can be described as music unburdened by preconceived chordal or time patterns and unconstrained by conventional harmonic structures. But it was also a music that imposed an almost unrealistic burden upon its listeners, a weight that, as it turned out, few were equipped to carry.

If the three predominant scales in the world are the pentatonic, which forms the basis of Chinese and Japanese music, the diatonic comprised of the black and white notes on the piano, and the maqam, common to the Arab world and India, it is the Western diatonic scale that has enjoyed the most widespread global reception. The genesis of these scales corresponds to distinct emotional states and cultural divergences. The maqam scale necessitates more precise intervals to reflect the predominantly tragic worldview prevalent in India and Islam throughout much of their history. Free jazz, in its quest for purity of expression, borrows heavily from the atonal and 24-tone maqam scale. This short-shrifting of the orthodox Western chromatic scale is not merely a technical departure; it is a statement of intent.

Free jazz shatters all established aesthetic rules. Or to cast a more charitable light upon its intentions, it endeavors to redefine, or reinvent our conventional understanding of aesthetics and beauty. This brave new aesthetic, or perhaps more accurately, anti-aesthetic, did not emerge ex nihilo, which raises the question:

Why would musicians consciously create a form of music that appeared to expressly, almost aggressively, keep the listener at arm's length? Free jazz was often so dense, so overwhelmingly powerful, so seemingly depleted of oxygen, that even the best-intentioned listeners found themselves unable to penetrate its sonic wall.

If the outsider is to understand the satisfaction this new music provides the composer and musician, he must view its development though both historical and psychological lenses.

Since their unasked-for arrival in America, Blacks have been systematically and brutally excluded from virtually all forms of participation in the nation they helped build. Just as it is a widely recognized psychological phenomenon of relationships, that the abused, when presented with the opportunity, often, and tragically, becomes the abuser. Since Blacks were economically and socially excluded, free jazz, in a perverse yet historically understandable inversion, afforded them the opportunity to become the excluder, which in America and Europe would have targeted the predominantly white audience. This may sound facile, or overly simplistic, but how else are we to account for a music that conjures up the image of an impenetrable fortress, seemingly designed to keep the listener out?

Free jazz weaponized music, and as an angry music it is without precedent. In John Coltrane's Expression (Impulse!) his final recorded album from 1967, the torrent of notes seem to issue from an automatic weapon. Before this sonic onslaught, the ear instinctively cowers, contracts, desperately seeking safe harbor from what sounds like machine gun fire masquerading as notation. Well-intentioned listeners, devoted jazz lovers, yearn for entry, for a point of connection, but find none. Instead, they find themselves facing a wall of sound. In a profound and deeply unsettling sense they are shut out, just as Blacks were unjustly shut out from every normal facet of life. The immediate effect is that the listener is left stranded, grappling with the question of what circumstance could have unleashed such anger and abuse, especially when juxtaposed against Coltrane's memorable collaboration with

Johnny Hartman

vocals1923 - 1983

However, the insurrectionary nature of free jazz did not go unnoticed by some of its critics who struggled to reconcile its brave new aesthetic with the more orthodox notion of musical artistry.

LJC, the London Jazz Collector, in its review of Archie Shepp's Magic of the Ju Ju (Impulse!, 1968) observes: "has abandoned the cool aesthetic of angular melodies and shimmering space, and replaced it with chaos and anger, in a raging fiery act of spiritual exorcism..."

Zotter, commenting on Coltrane's Expression, offers a similar assessment: "the cosmic dissonances, brought to their most extreme boundary (devoid of boundary), were now and forever abandoned to themselves, tossed there in a corner."

C. Michael Bailey, from All About Jazz, does not mince his words in his review of Ornette Coleman's album Free Jazz (Atlantic, 1961): "Without context, this music is effectively un-listenable... begins as a schizophrenic note salad, borne in chaos and given only a 'whiff' of direction. The music may best be described as the best New Orleans Dixieland exposed and mutated by radiation exposure. It is the phenomenon where the music, at first blush, sounds completely untethered."

Adducing the word 'whiff' in a musical context is arguably as revealing as the music that aroused the sensation, perhaps of the kind latrine orderlies are all too familiar with.

Thomas Cunniffe, referring to the master of dissonance, experimenter sans égal, Sun Ra, described his contribution to the genre as "joyful noise." Well, he got it half right.

Free jazz is insurrectional. At the expense of everything else, and with the compliance of the jazz elite and recording companies, self-expression is turned into a tyranny. Anger that once merely smoldered is liberated and transmuted into a form of music that ambushes instead of embraces. Black musicians do not simply cancel the mostly white audiences; they mow them down, render them helpless and confused vis-à-vis what they had come to expect and what is, in fact, delivered.

Under the auspices of free jazz, the piano, normally a melodic and harmonic anchor, is turned into a more percussive instrument, its keys struck with a force that often verges on violence. The saxophone, capable of unparalleled lyrical beauty, is transformed into what can only be described as a spit or shriek machine, its notes abrasive, its overall sound resembling a disgorgement or vomiting.

Earlier in the 20th century, atonal or dissonant music emerged as the white musician's expression, but it was not an angry music but rather an expression of alienation, of how the composer or musician felt in a world he no longer recognized. The music was the measure of a world gone to hell, of mass culture for whom a line of credit and a line of coke were the new gods on the block. Free jazz, in its own manner, prefigured the coming into being of the "Nowhere Man," immortalized in a song by

John Lennon

guitar and vocals1940 - 1980

However, the war free jazz waged against foundational aesthetics did not succeed. It is one thing to refuse to pander to an audience, it is altogether something else to disenfranchise it. If the critics managed to find a cozy niche for the movement in the history of jazz, it was only because the best white musicians, shameless epigones, bought into it. Imitation continues to be the highest form of flattery.

Free jazz failed to resonate with broader audiences because it violated what might be considered the non-negotiable laws of music aesthetics, an aesthetic evolved over thousands of years in respect to what constitutes an acceptable temporal interval (1/4, 1/8... 1/32) between the notes as well as the crucial spaces (silences) between them. It seems that no matter how elastic are the concepts of beauty and melody, they can only be stretched so far before they break, or, in the case of free jazz, snap back with jarring, punitive recoil. It is true that the 24-tone Arabic scale, with its micro-tones, appears to break these Western-centric rules, but the appreciation of that music is largely confined to the hard-scrabble life of peoples for whom the future, for much of their history, has held little promise. The premise and purpose of that music is to provide an alt-world, a temporary respite from the real world.

As for the apologists of free jazz, those who truly believe that we just do not get it, can we agree that the truth of where we stand vis-á-vis the position we take on a particular music is inescapably revealed in the music we consistently listen to and return to again and again in the privacy of our homes? I can shout to the world that I love the late Coltrane, but if I only listen to

Bill Evans

piano1929 - 1980

If, as Arthur Koestler observes, "a snob is someone who when reading Dostoyevsky is moved not by what he reads but by himself reading Dostoyevsky," I can't help but wonder what percentage of free jazz enthusiasts are snobs. The truth of who we are at any given moment is determined by what we spend our time on, or as Antoine de Saint-Exupéry writes in The Little Prince: "the value of the rose is the time I spend with it."

Finally, I must allow that I have made all manner of claim and presumption in this declarative essay. Since aesthetic judgments, by their very nature, cannot be rationalized, I cannot prove, as in mathematics, that one genre of music is inherently superior to another. I am simply presenting my critical arguments against, just as free jazz has entered its aesthetic into the public domain, where what works for one person or culture, may not work for another. Yet there is something to be said about music that possesses a global reach, that is able to find a permanent home in a foreign culture, and/or endures though time.

During the Montreal Jazz Festival just prior to Covid, I had occasion to attend concerts by Ornette Coleman and

Wayne Shorter

saxophone1933 - 2023

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Listen

Listen

Listen

Listen

Listen

Listen