Home » Jazz Articles » The Jazz Life » Does Talent Matter?

Does Talent Matter?

My friendЎҜs view of talent as some magic gift assumes that being the best singer, or the best piano player is synonymous in some ways with destiny. . . What is true, I think, is that every artist or performer has a responsibility to develop and refine a uniqueness of vision that makes them special, regardless of whether or not others appreciate that vision. But saying it is one thing, and living it another.

Charlie Christian

guitar, electric1916 - 1942

Not so long ago, another friend who wanted to be a novelist and had worked hard at it for several years without much success, asked me: "What's more important to artistic success? Talent, judgment, or perseverance?"

This felt like one of those argumentative things Jack might say to me sometimes when we were younger and out listening to music and ran out of anything more interesting to say to each other. But it's a kind of "brain worm" (cousin of an "earworm") too. Once spoken it lingers, like an unwelcome party guest who won't go home.

Although my friend's nonfiction has been published, he had decided to quit writing because he just couldn't find a publisher. His fiction would never get published, he said, because he just wasn't talented enough, regardless of how hard he worked at it.

I disagreed with him. At one point in our discussion he said that if a less talented person could catch up with someone who had a genuine gift for their art form through hard work alone, it would mean anybody could sing like

Frank Sinatra

vocals1915 - 1998

Michael Brecker

saxophone, tenor1949 - 2007

Jerry Bergonzi

saxophone, tenorb.1947

There's an appealing superficial obviousness to my friend's observation, but I don't buy it. I work with writers and musicians every day; I see the "talent" in my teenage son and I know, for that talent to mean something, the hard work he must choose to put in daily into mastering not just the violin but jazz itself. And I see the fulfillment and pride of achievement he feels when he performs well and is recognized for it.

The observation that some people can do some things better than others is why I quit playing music for a while 30 years ago. I did it for a number of reasons, but the truth was I was in awe and also despondent of things friends did musically, many of them great players, that I could not. My friend told me he decided to quit writing because of that story, which I had told him casually over lunch some years before. But he wasn't paying attention to the fact that when my son started playing the violin, I started practicing once more and found I enjoyed it so much I eventually started playing in public again.

My friend's view of talent as some magic gift assumes that being the best singer, or the best pianist is synonymous in some ways with destiny. But it's truer to say that some people have, for example, innately better hand-eye coordination than others. But so what? It's why we can get into (somewhat pointless) beer soaked arguments about who's the better jazz guitarist—

George Benson

guitarb.1943

Pat Martino

guitar1944 - 2021

In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell cites a study done in the 1990s by K. Anders Ericsson (Dept. of Psychology, Florida State Univ.) on music students. In true British tabloid-press fashion, Gladwell overbroadly concluded from the report that elite musicians averaged 10,000 hours of practice each, while the less able only practiced 4,000 hours. It was the hard work that did it, was the message.

But this conclusion was disputed as simplistic by Ericsson in a letter to the NY Times. Ericsson's letter made a better, subtler point:

Our paper found that the attained level of expert music performance of students at an international level music academy showed a positive correlation with the number of solitary practice hours accumulated in their careers and the gradual improvement due to goal-directed deliberate practice.

In other words, the most accomplished students didn't just practice for hours on end in order to get better, they used that time to focus on mastering technical skills designed to improve performance and express their creativity; they developed their skills using external rewards as motivation, such as pay, or concert performances; and they participated in any kind of practice that explored their various skills and was inherently enjoyable, like jamming/playing with other people. So, according to Ericsson, it's not talent, nor even endurance of long hours put into mastering your craft that counts, but what you practice that is so important. It's also true that at some point fairly early on, true craftsmen and women usually fall in love with practicing to the point where it becomes a kind of daily meditation.

If my friend was right, then in Ericsson's study the "super talented" should have risen to the elite level with less effort than their peers. No one did. In fact, the data showed a direct correlation between hours of correct practice, and achievement. Wise journeyman study wins out, it seems.

An example of all this can be glimpsed in the sad story of the (fairly unknown) brilliant jazz guitarist

Billy Bean

guitarb.1933

Charlie Parker

saxophone, alto1920 - 1955

Wes Montgomery

guitar1923 - 1968

Joe Pass

guitar1929 - 1994

Dennis Sandole

b.1913

John Coltrane

saxophone1926 - 1967

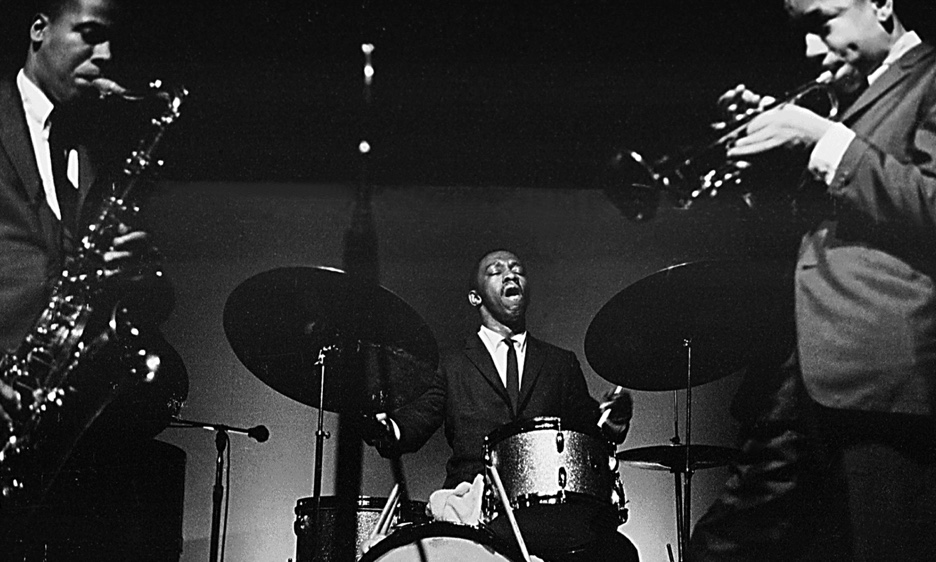

I may have mentioned this before, but for me the best definition of talent is by the iconic jazz drummer

Art Blakey

drums1919 - 1990

Implied in my friend's question is another that sets my teeth on edge—what do we mean by "success"? Financial success and fame require of the artist an overtly commercial sensibility that may appeal to the masses e.g., Justin Bieber, or Lady Gaga, but artistically in terms of talent are they really comparable to, say, Frank Sinatra or Rene Fleming or

Aretha Franklin

vocals1942 - 2018

But I believe, even now, art should not be just about money, because inevitably then it becomes shaped by a fear of offending people. It makes sense to me that art has to be intellectually and emotionally challenging, because it attempts to ask interesting questions and make us think differently about the world we live in. So it's likely to have a small audience at first, which will hopefully grow over time. We hope, further, that audiences will enjoy our work enough to look to see if there is more by us. Once in a while something may catch unexpectedly, and a new phenom is born from base clay, but you can't really plan for that.

I'd argue that artistic success is true admiration from one's peers. It's hard won and not often bestowed on the popular (though there are obvious exceptions). Charlie Parker, for example, considered one of the greatest jazz musicians of all time, was not hugely popular among audiences at the time.

Louis Armstrong

trumpet and vocals1901 - 1971

There is no separating talent from the other qualities, it's just one piece of a complex puzzle. And at some point, becoming the "best" at whatever you do becomes replaced by a realization that talent is really about our commitment to undertake an inner journey and share some of the treasures we find. In the case of my novelist friend he decided he didn't want it (whatever "it" is) badly enough to really work to get where he needed to be.

In the end, I think "talent" is about the determination to discover who we are, and what we want to say and the effort to do it as well as we can. It is, what it is, nothing more or less. The real challenge is to say something unique and honest, and say it with grace and energy. After that, it's in the lap of the gods whether or not others connect with it.

Photo credit: Mosaic Images, LLC

Tags

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Buy Now

Buy Now