Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Playing Jazz In Socialist Vietnam: Quy?n V?n Minh and Ja...

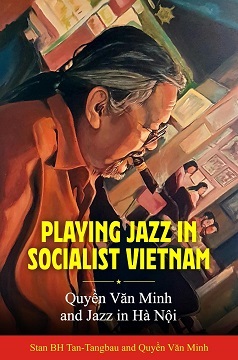

Playing Jazz In Socialist Vietnam: Quy?n V?n Minh and Jazz in Hanoi

Playing Jazz In Socialist Vietnam: Quy?n V?n Minh and Jazz in Hanoi

Playing Jazz In Socialist Vietnam: Quy?n V?n Minh and Jazz in Hanoi Stan BH Tan-Tangbau and Quy?n V?n Minh

269 Pages

ISBN: 9781496836335

University Press of Mississippi

2021

That an aspiring Vietnamese musician in this day and age can study jazz at conservatoire level in Hanoi, or jam three hundred and sixty-five days a year in a jazz club in the Vietnamese capital, is largely thanks to the lifelong efforts of saxophonist Quy?n V?n Minh to promote jazz in his country of birth. Rather than offering a comprehensive history of jazz in Vietnam, Playing Jazz In Socialist Vietnam... provides a vivid portrait of one man's musical crusade.

Co-written by Quy?n and Southeast Asian studies scholar Stan BH Tan-Tangbau, this equal parts interview transcript and third-person narrative charts Quy?n's journey as a musician, as a jazz fan and ultimately as a jazz advocate on a national level. Born in 1954, Quy?n's remarkable story unfolds during The Indochinese Wars and the transitional period of Vietnam's modern, post-colonial history. It is a story of perseverance in the face of overwhelming odds—economic, political and cultural.

But to describe Quy?n as a saxophonist is to sell him short. Almost single-handedly Quy?n raised the profile of the saxophone in Vietnam from an instrument of light entertainment to one worthy of conservatoire-level study. He took jazz from its outlier status as "music of the enemy" and brought it into the Vietnamese mainstream, both as popular music and as music belonging on the same prestigious stages as classical or traditional music. He was also the first musician to use Vietnamese traditional music as a prism through which jazz could reach new audiences. So, saxophonist, yes, but also a pioneer, an educator and in many ways, a radical.

Then there is Minh's Jazz Club, the first jazz club in Communist-era Vietnam, which opened its doors in 1997. Quy?n ran the club for a quarter of a century before passing the reins over to his son, Quy?n Thi?n ??c, a respected saxophonist in his own right, in 2017. There is something wonderfully Quixotic about the travails the elder Quy?n overcame to run a jazz club in a country where, by his own admission, jazz has a "minuscule" following.

The first incarnation of Minh's Jazz Club was forced to close after just three months by a government redevelopment program. Having risen from the ashes, the second version of Minh's Jazz Club lasted less than a year, forced to close for similar reasons. Undeterred, Quy?n upped sticks once again, this third attempt at running a jazz cub in Hanoi's Old Quarter lasting a full decade before the lease expired and the bulldozers moved in. A fourth rebirth lasted just a few months before Quy?n was forced to relocate yet again. Since 2014, home to Minh's Jazz Club has been at 1 TrЁӨng Ti?n, behind the Hanoi Opera House.

As Tan-Tangbau notes: "For those who grew up with the Cold War, who are familiar with Vietnam's painful experiences during Th?i Bao C?p (the Subsidy Period) and the Indochina wars, who witnessed the labored process of the ??i M?i reforms, and who experienced the persistent cultural surveillance in Vietnam before the digital revolution changed the world, the existence and longevity of Minh's Jazz Club is something hugely significant. "

It is perhaps surprising that Vietnam's first jazz club should have opened in Hanoi. The country's partition—following the defeat of the French in 1954—saw foreign music effectively banned in North Vietnam, while in the US-backed South, western popular music thrived. Growing up in 1960s Hanoi, there was practically nowhere for Quy?n to see or hear jazz, and as the authors relate, people were afraid to listen to music that met with the Communist government's disapproval.

A chance exposure, to what the authors assume was probably Willis Conover's Voice of America program in 1968, lit a fire under Quy?n. The music moved him, though he recounts that he did not even know that it was called jazz. Encounters with jazz were rare, but always significant. In 1972, Quy?n was able to listen to and painstakingly transcribe a jazz album at a friend's house. The unnamed album was a prized artifact brought back from a study trip in Eastern Europe.

It was not until after reunification in 1975, on a trip to Saigon, that Quy?n purchased his first jazz album. Even then, he simply asked an elderly store owner if he had: " any music cassette tapes of Black musicians." Quy?n describes the cover of the cassette he purchased as featuring: " a band of Black musicians with Black lady singing into a microphone." The jazz-hungry musician transcribed all the songs without knowing who he was listening to, wearing the tape out in the process.

The lack of access to American jazz, especially vinyl, and the restricted orbit in which Vietnamese musicians existed in those times, can be gauged by the fact that Quy?n was converted to the soprano saxophone, not by the music of

John Coltrane

saxophone1926 - 1967

Wayne Shorter

saxophone1933 - 2023

By any yardstick, Quy?n's rise from self-taught-musician to the position of lecturer at the Vietnamese National Academy of Music is an extraordinary story. His path included years playing clarinet in the government Song-and-Dance-Troupes that toured the country providing entertainment for the Vietnamese troops fighting the Americans.

It was during such tours, beginning in 1970, that Quy?n encountered the music of Vietnam's many ethnic groups, music that inspired certain of his compositions, though he insisted on using his own melodies.

On a trip with the Thang Long Song-and-Dance Troupe to Berlin in 1987, Quy?n heard jazz everywhere he went. He describes the experience as a turning point, one that set him on a mission to pursue this music professionally, introduce it to the Vietnamese public and legitimize it.

A major part of Quy?n's story centers around three 'solo' performances at Hanoi's Opera House that took place in 1988, 1989 and 1994. These high-profile concerts came just as the ??i M?i economic reforms began to signal a very gradual relaxing of the political and social climate. On this grand stage Quy?n showcased the saxophone and jazz—groundbreaking symbolism in a country where only a few years earlier such music would have been deemed as "unrevolutionary."

The boldness of Quy?n's program—which also contained western classical and Vietnamese chamber music—-becomes clear in learning that he felt it prudent not to include the word 'jazz' in the program notes for the first recital. Instead, the jazz standards that he performed with a band were listed as "international light music." As he recalls: "I dared not use the term 'jazz' then. In those days, no one would dare to proclaim, 'I play jazz!' Those years in the 1980s, music in Vietnam was subjected to very strict censorship."

Two chapters place Quy?n's jazz odyssey in the wider context of jazz history in Asia, and against the backdrop of the Cold War, with an emphasis on the Socialist Bloc countries of Central and Eastern Europe. If there is a common thread, it is that jazz's fate, everywhere it seems, was buffeted by the powerful winds of ideology.

By the time of his 1994 Opera House recital, the climate had changed sufficiently that Quy?n felt comfortable listing compositions by

Charlie Parker

saxophone, alto1920 - 1955

Antonio Carlos Jobim

piano1927 - 1994

Quy?n's is also a story of sacrifice and ingenuity in economically challenging times, while also raising a family. No gig, no matter how casual, it seems, was ever turned down. Quy?n describes how he learned to repair instruments and started teaching to boost his income. And in these days of rampant consumerism and disposable culture, it is humbling to consider that a bicycle represented serious collaterial.

A constant feature of Quy?n's trajectory is his tireless dedication to practice. Even when stationed in the Vi?t B?c highlands with a song-and-dance troupe, the determined Quy?n would climb further up the mountain so as not to disturb his colleagues while practising.

Over the course of half a century, and in the most difficult of circumstances, Quy?n has climbed his own mountain and planted the flag of jazz, forging a path for others to follow. It is an inspiring tale that marks a major step in the chronicling of the history of jazz in Vietnam.

Tags

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Buy Now

Buy Now