Home » Jazz Articles » Live Review » Winter Jazzfest 2025: The Once and Future Music

Winter Jazzfest 2025: The Once and Future Music

Courtesy Adam Beaudoin

This year's Winter Jazzfest revealed a music looking both forwards and backwards at once, attempting to assert its own identity and direction while still responding explicitly to the history of the genre.

New York, NY

January 9-15, 2025

Impressions of A Love Supreme

We are standing in a line outside the venue, waiting in the January chill to listen to nearly two dozen musicians perform and pay tribute to

John Coltrane

saxophone1926 - 1967

Sun Ra Arkestra

band / ensemble / orchestrab.1956

McCoy Tyner

piano1938 - 2020

"It all has to do with it.

Thank you God.

Peace.

There is none other.

God is. It is so beautiful.

[...]

Let us sing all songs to God.

[...]

With all we share God."

Attempting to cover or adapt A Love Supreme is a somewhat quixotic gesture, although it has been done, most notably by

Wynton Marsalis

trumpetb.1961

A Love Supreme was the product of one of jazz's greatest quartets at the height of their collaboration and creativity, working largely improvisationally from sketches to frame an ecstatic concept that existed in the bandleader's inner ear. It is a supplication, a prayer, an offering, to the universal spiritual consciousness that Coltrane had begun to experience in the lived world. There is no recreating that fervency, just as there is no recreating the unique improvisational dialogue that these four musicians communicated in.

This evening, however, John's son

Ravi Coltrane

saxophone, tenorb.1965

David Virelles

pianob.1983

Jeff Tain Watts

drumsb.1960

Dezron Douglas

bassGenerally, the performances were more muscular and less introspective than those on the record, though compelling in their own right and on their own terms. Watts played with a stylistic versatility and variety that guided the spirit of the group and shaped its interpretive ebb and flow. Douglas' bass was forceful and driving, whether undergirding one of Virelles' harmonic flights or in his visceral solo that transitioned from "Pursuance" into "Psalm." Virelles, who moved back and forth between acoustic piano and Rhodes; and Coltrane, who abandoned Tenor after the chanted portion of "Acknowledgement," moving to Sopranino, Alto, and Soprano respectively for the following three movements; both incorporated elements of free improvisation into their playing that, while not unfamiliar to the musical landscape that A Love Supreme emerged from, had been conspicuously and intentionally absent from its musical language. Ultimately, though, all these differences worked, individually and as components of a coherent whole. It was enough for this to be an A Love Supreme, with its own unique conception, informed by the intervening decades.

Remarkable as it was, this set was only the first part of the concert. Billed as "Impressions: Improvisatory Interpretations on A Love Supreme," featuring a diverse lineup of early-and mid-career improvising musicians, it promised an examination of the continuing impact of the piece on jazz's present-day—the vanguard of the music scene reflecting on and responding to this landmark of the medium.

A Love Supreme is more than just John Coltrane's creative peak. It is enduringly beloved, and one of the best-selling jazz albums ever. Its influence on the generations of jazz musicians that followed is enormous. It was the defining statement of what came to be known as "spiritual jazz," a kind of post-modal not-quite-free jazz that turned to existential and metaphysical themes. Its descendants were plentiful in the 1970s, and its influence can still be heard today in the work of artists like

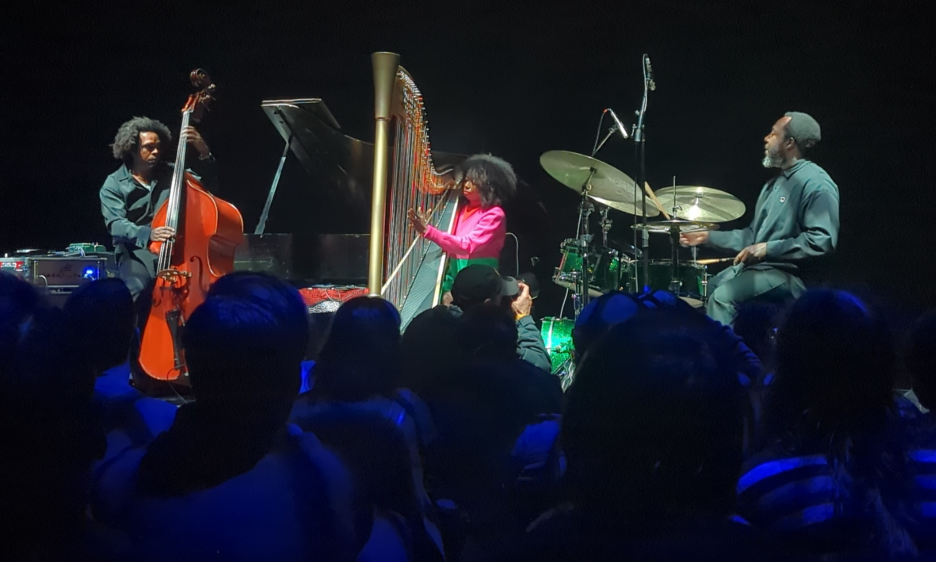

Brandee Younger

harpb.1983

Amirtha Kidambi

drumsA Love Supreme is a creative touchstone for many in the contemporary scene, and Winter Jazzfest had assembled an impressive cross-section of forward-looking jazz musicians*. But in the wake of the quartet's presentation of the entire suite, it wasn't immediately clear how they planned to program such a billing. Would they be forming groups to play individual movements? Improvising on themes from the piece? Presenting their own compositions that show them in dialogue with the album? Much to their credit, the set instead turned out to be a sort of improvisatory round robin, that while barely touching on the literal musical themes of A Love Supreme, still powerfully evoked its spiritual ones.

It began with the three drummers improvising together: a sparse soundscape of cymbal creaks, brush flutters, and errant hits that gradually layered and built into an ever-shifting groove. Overall began to whoop, hoot, and aspirate into a mic, punctuating the roiling rhythm with exhortations of "the spirit is back." As they played, Sanchez and Evans entered, sitting down respectively at an acoustic grand and a Rhodes. The duo began; the drums decrescendoed and left the stage. The keyboards improvised freely: duelling ideas, weaving together and apart in delicate interplay. Then, as they themselves had displaced the drummers, the bassists walked on and gently picked up their thread. They too began sparsely: tapping their instruments, scratching with their bows, short punctuations of pizzicato, building to a collective free improvisation that suddenly resolved into a triad. Each voice began to move, stretching and varying the harmony by degrees until it finally broke down into its constituent pieces, which settled into a duo groove descanted by Obomsawin's arco. From this flow and ebb of contiguity and individual line emerged for the first and only time a motif from A Love Supreme, which itself quickly began to morph and fade.

From just offstage, the clatter of chimes (strung hanging from the body of Newsome's soprano sax) announced the entry of 6 saxophonists whose forceful exhalations overwhelmed those of us near the stage. The saxophones, fittingly, proved the climax of this exploration, their interweaving lines combining into a sublime wall of sound: one unitary, collective, multi-voiced entity. At once frenetic and peaceful, it was enveloping, denaturing. For a brief, profound moment, there was no performer and no audience, no self; there was only sound.

"Words, sounds, speech, men, memory, thoughts,

fears and emotions—time—all related...

all made from one... all made in one."

Inevitably, after climax, denouement. Vibraphone, guitar, trumpet, trombone, and tuba entered and began to play, at first inaudible beneath the ebbing bliss of saxophones. Then, too, the saxophones left the stage and revealed the music they covered. Now the instrumentation was more distinct, the brass sometimes melding together, sometimes separating into their own individual flights of melody. Beneath them, the guitar soundscape, filtered through layers of effects processing, swelled and receded. The vibraphones, not overly amplified, maintained a slight, sweet chiming, like bells at a distance. While the musicians were playing no less beautifully, the heterogeneity brought a psychic ebb, a return into the self.

After some time, the drummers returned, punctuating the brass with the light tipping of a ride cymbal, the clang of a bell, a roll of timpani. The guitar evaporated completely into its electronic manipulation. The horns faded. The creak of a cymbal marked the end. This collective devotional was a true, unvarnished display of A Love Supreme's resonance in the hearts and ears of today's jazz musicians. As Coltrane wrote:

"One thought can produce millions of vibrations

and they all go back to God ... everything does."

*Drums:

Kassa Overall

programming

Allison Miller

drums

Nasheet Waits

drumsb.1971

Angelica Sanchez

piano

Orrin Evans

pianob.1975

Linda May Han Oh

bass, acousticb.1984

Ben Williams

bass, electric

Mali Obomsawin

bass, acoustic

James Brandon Lewis

saxophone, tenorb.1983

Jordan Young

drumsb.1978

Jordan Young

drumsb.1978

Melissa Aldana

saxophone

Tomoki Sanders

saxophoneb.1994

Emilio Modeste

saxophone

Kenny Warren

trumpet

Kalia Vandever

tromboneb.1995

Theon Cross

tuba

Rafiq Bhatia

guitar

Joel Ross

vibraphoneSuite Freedom: A Candid Records Showcase

The Candid Records showcase at NuBlu on opening night, like so many other features of this year's Winter Jazzfest, revealed a music looking both forwards and backwards at once, attempting to assert its own identity and direction while still responding explicitly to the history of the genre.Candid Records has gone through many incarnations over the years. At its origins, from 1960-1964, it was a home for avant-garde musicians including

Charles Mingus

bass, acoustic1922 - 1979

Cecil Taylor

piano1929 - 2018

Abbey Lincoln

vocals1930 - 2010

Jaki Byard

piano1922 - 1999

Clark Terry

trumpet1920 - 2015

Steve Lacy

saxophone, soprano1934 - 2004

"

data-original-title="" title="">Andy Williams, who kept the catalog in print. In 1989, it was bought by a UK label and distributor, who reissued the back catalog on CD, and released new albums by

"

data-original-title="" title="">Andy Williams, who kept the catalog in print. In 1989, it was bought by a UK label and distributor, who reissued the back catalog on CD, and released new albums by

Kenny Barron

pianob.1943

Dave Liebman

saxophoneb.1946

Lee Konitz

saxophone, alto1927 - 2020

Ingrid Laubrock

saxophoneb.1970

Irene Kral

vocals1932 - 1978

Terri Lyne Carrington

drumsb.1965

This concert, then, was a display of the breadth and depth of talent on today's Candid Records. It featured short sets from four younger artists that present dramatically different conceptions of what jazz means and sounds like in the present moment.

Simon Moullier

vibraphone

Lex Korten

pianob.1994

Matthew Stevens

guitarb.1982

Walter Smith III

saxophone, tenorb.1980

Esperanza Spalding

bassb.1984

Vocalist

Zacchae'us Paul

keyboards

Milena Casado

flugelhorn

Morgan Guerin

multi-instrumentalist

Kanoa Mendenhall

bass, acoustic

Jongkuk Kim

drumsThe headliner on this program was Carrington's presentation of the

Max Roach

drums1925 - 2007

Oscar Brown Jr.

vocals1926 - 2005

"When I listen to the original album, I feel a heaviness. I feel like these men are really dealing with this thing from a very deep place, but I can also feel the anger. I feel that sense of darkness around the theme. For our cover of We Insist!, there's a lot of joy in it as well. We're still dealing with the themes, but from where I stand, there's a place in the music for me that is celebratory, joyous. I want to make people feel good. I want to make myself feel good. [...] I'm dealing with a lot of heavy issues, but it doesn't take away my light."

Above and beyond any changes to the compositions and arrangements, the makeup of the ensemble already begins to bring the piece into a contemporary context. The band included a stylistically diverse group of younger musicians, including several drawn from the new Candid Records roster. In addition to Carrington on drums, there was

Christie Dashiell

vocalsThe set itself essentially followed the order of the original album, excepting the addition of two new, spoken-word pieces, and the omission of "Triptych: Prayer / Protest / Peace," which whether due to limited stage time or a studio-process-oriented composition will have to wait for the album's release this spring.

"Driva'man" opened with the same vocal acapella as in the original arrangement, and Dashiell instantly captured the room, sounding more like

Nina Simone

piano and vocals1933 - 2003

The first big shock, however, came when the band joined her. Where Roach and Brown's arrangement featured horns playing bluesy and dissonant cluster chords in a slow, swinging 5/4, punctuated by a regular rimshot, Carrington kept only the meter, replacing the rest with a vibrant Afro-Cuban groove. Musically, this worked excellently, giving Dashiell an active palette to phrase against, and opening a space for Stevens to stretch out, an octave pedal lending his solo a timbre resembling a steel-drum. In context, however, the arrangement undercut the lyrical content, creating an uncomfortable juxtaposition of joyful music with the description of a slave driver's abuse. It also imparted to the beginning of the suite a rhythmic exuberance that didn't enter the original until the penultimate "All Africa," radically reshaping its emotional arc.

"Freedom Day" made an even greater departure from its source material, and one that worked much better thematically. As with "Driva'man" Carrington discarded the original's three-horn main theme, interlude, and backgrounds. Then she dramatically slowed the piece down, and set the melody over a vibey neo-soul vamp. In this context, the lyrics speak with a skepticism or even cynicism about the true extent of the titular freedom that in Roach and Lincoln's delivery was delivered as a frenzied mixture of anxiety and exhilaration. This tension was reinforced by a new section that concludes the piece, with the repeated lyric "Freedom Day is every day of freedom." This wasn't tautology, but an acknowledgement that freedom is a shifting reality and an ongoing struggle.

"All Africa" was a fairly straightforward delivery of the original, though one where the layered polyrhythms of multiple percussionists were spread out across the drums, bass, and guitar. They provided ample space for Casado and Stevens to stretch out and improvise, both over the usual sections of the composition and the triple-meter backbeat vamp that resolved out of the rhythmic variation to close the song.

Departing from the Roach/Brown compositions, they moved into one of two spoken word pieces, Carrington's original additions to her adaptation of the suite. This one, "Boom Chick" was an ambling, artlessly literal tribute to Max Roach, delivered by the group's dancer Christiana Hunte, over a simple repeated drum figure that Carrington encouraged the audience to participate in by stomping and clapping, or vocalising the beat. At once unobjectionable and uninteresting, it was an incongruous inclusion, lacking in both the anger Carrington identified in Roach's We Insist! and the joy she spoke of bringing into her own adaptation.

"Tears for Johannesburg" was, like "All Africa," a faithful adaptation that still allowed some room for surprises. For perhaps the first time in this performance, some of Roach's horn voicings were preserved, shared across the trumpet and guitar. The original's meter was elaborated, every fourth bar shortened by a beat. After stating the melody, Dashiell unleashed a stunning improvisation, trading back and forth cannily with Stevens. They modulated for Casado to take a solo, then returned to a restatement and deconstruction of the haunting vocal theme.

This would have been a fine place to wrap up, but they had one more accompanied spoken-word piece to end the set. More directly than at any point before, "Freedom Is" literalized Carrington's attempt to bridge the aforementioned gap between her reading of the historical context for the Freedom Now! Suite and the contemporary sociopolitical landscape, to recenter some of that male anger that she perceives as defining the original. So what is freedom, in the present day, to Carrington? Mostly, it's a progressive vision of social community that promotes justice and equity of race and gender:

"Freedom is going to elementary school without walking through a metal detector.

[...] Freedom is knowing that you can vote, and it will count.

Freedom is no walls, and no cages, and no glass ceilings either.

Freedom is not a male thing; in fact, freedom is understanding gender

to be a social construct, and falling wherever you choose on the gender spectrum.

Freedom is not having to deal with legislation that tells you what to do with your body,

Or who you should love. Nor being trafficked, nor working in a sweatshop,

and definitely not being physically abused or assaulted.

Freedom is knowing that your cries for help will not fall on deaf ears,

and it is being perceived and responded to as an equal.

[...] It is knowing that your mistakes will be seen as mishaps,

and not a reason to put you in prison,

and knowing you'll have help getting a fresh start after.

[...] It is being seen by those who can't look away any more."

There's a clarity and consistency of message here, but it does feel missing the fire and insistence of Roach and Brown's ideological stance, rooted directly in the civil rights movement. Theirs was not just Freedom, but Freedom Now. And one important issue here, I suspect, is Carrington's complicated relationship with capitalism and the desire to benefit from it (even while the capitalist greed-drive is at the very root of the injustices she articulates.) Because she also defines freedom in terms of consumption:

"Freedom is binge-watching Bridgerton for the third time.

It's when you go shopping without looking at the price of tags,

and simply say 'put it on my tab.'

Freedom is winning the womb lottery of generational wealth.

[...] It's being comfortable enough to talk to strangers:

cashiers, car dealers, what have you,

without worrying about judgement or bogus stereotypes.

[...]Freedom is taking an Uber instead of the subway

because the neighborhood you're going to is a little sketchy

[...] Freedom is being able to get vegan food wherever you go, and it tasting good.

Freedom is going to Hawaii to bake in the sun, or cool off in the water,

when you're having withdrawals from addiction."

Absence of financial insecurity, access to healthy food, the ability to travel—these are all meaningful features of a minimally privileged life in our contemporary society. But this consumerist vision of "freedom" starts to feel uncomfortably like its own sort of servitude. At one point in the poem, she addresses this conflict directly:

"Freedom is to exist in a capitalist society,

conscious that your purchases will not support child or slave labor.

Freedom is being able to make the decision not to live in a capitalist society."

As the saying goes, "there is no ethical consumption under capitalism," and it seems that Carrington ignores that fundamental incompatibility. How, after all, does she imagine that "the decision not to live in a capitalist society" and "winning the womb lottery of generational wealth" could possibly coexist as equal conceptions of human freedom?

From the stage, she described this piece as an "attempt at modernizing the themes a little bit... times change, and so I wanted to bring in some new things for us to resist and insist upon." And there is a wealth of beautiful writing and playing in this adaptation. But I'm left wondering whether a non-revolutionary We Insist! is inherently a compromised one.

Strata-East Rising

Candid Records wasn't the only label reintroducing itself and touting its historic back catalog at Winter Jazzfest. Almost a week later, at the end of the festival, the legendary (and until this year, out of print) label Strata-East Records presented their own showcase. And while Candid had programmed short spotlights for their new artists before bringing out their historic material, Strata-East took a decidedly different approach, featuring a rotating blended lineup of the label's original artists playing alongside a wealth of younger talent.Strata-East was founded in 1971 by trumpeter

Charles Tolliver

trumpetb.1942

Stanley Cowell

piano1941 - 2020

Clifford Jordan

saxophone, tenor1931 - 1993

Billy Harper

saxophoneb.1943

Gil Scott-Heron

vocals1949 - 2011

Pharoah Sanders

saxophone, tenor1940 - 2022

Weldon Irvine

piano

Cecil McBee

bassb.1935

This spring, Strata-East relaunches, reissuing its back catalog on CD and LP (and, yes, streaming) along with new releases from a roster of contemporary artists. While the astounding array of musicians playing in this concert included

Christian McBride

bassb.1972

Luis Perdomo

pianob.1971

Endea Owens

bass

Camille Thurman

saxophoneb.1986

Jon Batiste

pianob.1986

Keyon Harrold

trumpetMost of the set drew on tunes from their back catalog, and it did feel at times more like a retrospective than a reinvention. The performances themselves, of course, were exceptional. Tolliver was lively and expressive, an expert leader as well as soloist. Owens was a force of nature on the bass, and in conversation with Hart's magnetic drumming made for a propulsive rhythm section with a profound, swinging pocket. Each participant in the slowly rotating ensemble was a master—even just Perdomo and McBride would have made for a riveting concert, but the sheer density of talent on stage was dizzying. Amid all that excellence, though, Batiste may have stolen the show in his one appearance, with a searching, exploratory solo improvisation that slowly gave way into an impossibly soulful groove, joined by McBride, Jordan, and Harrold, leading into a mesmerizing performance of Gil Scott-Heron's "The Bottle."

It's hard to say what perspective the new Strata-East will bring to the already-rich world of contemporary jazz recordings, but after this show two things are clear. Tolliver has as good an ear for the jazz scene today as he did in the '70s, and their back catalog offers a wealth of deep, interesting music that today's listener will be lucky to have accessible once again.

Tags

Live Review

Brandee Younger

Adam Beaudoin

United States

New York

New York City

John Coltrane

Sun Ra Arkestra

McCoy Tyner

wynton marsalis

Ravi Coltrane

David Virelles

Jeff Tain Watts

Dezron Douglas

Amirtha Kidambi

Kassa Overall

Allison Miller

Nasheet Waits

Angelica Sanchez

Orrin Evans

Linda May Han Oh

Ben Williams

Mali Obomsawin

James Brandon Lewis

Sam Newsome

Jordan Young

Melissa Aldana

Tomoki Sanders

Emilio Modeste

Kenny Warren

Kalia Vandever

Theon Cross

Rafiq Bhatia

Joel Ross

Candid Records

Charles Mingus

Cecil Taylor

Abbey Lincoln

Jaki Byard

Clark Terry

Steve Lacy

Andy Williams

Kenny Barron

Dave Liebman

Lee Konitz

Ingrid Laubrock

Irene Kral

Terri Lyne Carrington

Simon Moullier

Lex Korten

Matthew Stevens

Walter Smith III

Esperanza Spalding

CHRISTIAN SCOTT

Zacchae'us Paul

Milena Casado

Morgan Guerin

Kanoa Mendenhall

Jongkuk Kim

Max Roach

Oscar Brown Jr.

Christie Dashiell

Christiana Hunte

Nina Simone

Strata-East Records

Charles Tolliver

Stanley Cowell

Clifford Jordan

billy harper

Gil Scott-Heron

Pharoah Sanders

Weldon Irvine

cecil mcbee

Christian McBride

Luis Perdomo

Endea Owens

Camille Thurman

Jon Batiste

aja monet

Keyon Harrold

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Brandee Younger Concerts

Oct

23

Thu

Brandee Younger Trio

The FreightBerkeley, CA

Oct

27

Mon

Brandee Younger Trio

Dakota Jazz Club & RestaurantMinneapolis, MN

Oct

28

Tue

Brandee Younger Trio

Dazzle Jazz ClubDenver, CO

Oct

28

Tue

Brandee Younger Trio

Dazzle Jazz ClubDenver, CO

Nov

3

Mon

Brandee Younger

Eiffel M?helyházBudapest, Hungary

Mar

13

Fri

The Brandee Younger Trio

All Saints' Episcopal ChurchAtlanta, GA

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Go Ad Free!

To maintain our platform while developing new means to foster jazz discovery and connectivity, we need your help. You can become a sustaining member for as little as $20 and in return, we'll immediately hide those pesky ads plus provide access to future articles for a full year. This winning combination vastly improves your AAJ experience and allow us to vigorously build on the pioneering work we first started in 1995. So enjoy an ad-free AAJ experience and help us remain a positive beacon for jazz by making a donation today.

New York City

Concert Guide | Venue Guide | Local Businesses

| More...

Buy Now

Buy Now