Home » Jazz Articles » Under the Radar » Blue Highways and Sweet Music: The Territory Bands, Part II

Blue Highways and Sweet Music: The Territory Bands, Part II

Jazz came to America three hundred years ago in chains.

—Paul Whiteman

Part 1 of Blue Highways and Sweet Music: The Territory Bands looked at the roots, drivers and challenges of the travelling groups who brought jazz music to the non-urban areas of the Southern Plains, through one-night-stands, in often impromptu venues. A black phenomenon, often misappropriated by white musicians, promoters, record labels and venues, the most active period of territory bands coincided with the rise of post-slavery American racism. In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan reached its peak membership of more than four million, openly functioning as a guerrilla faction of the Democratic Party in the South and intimidated blacks with extreme violence. The discriminatory Jim Crow laws that began after the Civil War, flourished well into the 1940s and the black music that so many middle-class whites found liberating, excluded the very people who created that music.

In the era of the territory bands, it was more often the media, critics and cultural institutions that usurped black musical culture, as opposed to the white musicians and band leaders themselves. One of those white musicians happened to be the press-designated "King of Jazz," of whom, in 1919, the Pasadena Evening Post said: "the friends of Mr. Whiteman have with much enthusiasm bestowed the title of "King of Jazz" upon him." While

Paul Whiteman

composer / conductor1890 - 1967

Mildred Bailey

vocals1907 - 1951

Billie Holiday

vocals1915 - 1959

(J. H. Sears, 1926), written with Mary Margaret McBride, Whiteman opens the first chapter with this stark acknowledgement: "Jazz came to America three hundred years ago in chains. The psalm-singing Dutch traders, sailing in a man-of-war across the ocean in 1619, described their cargo as 'fourteen black African slaves for sale in his Majesty's colonies.' But priceless freight destined three centuries later to set a whole nation dancing went unnoted and unbilled..." Whiteman's group, by virtue of his worldwide fame, is an unlikely candidate to qualify as a territory band, having quite a few regular bookings in locations such as New York, Paris and London. Nonetheless, he toured all forty-eight of the then incorporated states by his own account with a particular focus on the Great Plains locations of Denver, Minneapolis, Topeka, St. Paul, Grand Rapids, Battle Creek, Kansas City, and Cleveland. As the economy of the US slowed down in its approach to the Great Depression, the consolidation of talent became a matter of survival for many bands and Whiteman was not alone in the move north.

The Great Plains

During World War I agriculture in the Midwest had largely converted to wheat farming as a means of cheaply feeding the troops. With the end of the war, demand for the crop dropped. Agriculture was the primary business in the rural Midwest and farmers were feeling the effects of a downturn long before the crash of 1929. With the start of the Great Depression an already struggling economy hit rock bottom and beginning in 1933 the catastrophic drought that came to be known as the Dust Bowl, forced half a million residents from their homes. Populations of six states plunged as did disposable income. Many of the travelling bands were no longer sustainable, further concentrating the hubs for territory bands and drawing more musicians to the remaining music centers. Kansas City, in particular, benefitted from the migration, where under the corrupt political regime of its mayor, Tom Pendergast, the city was a wide-open mecca for entertainment and vice. The income generated in Kansas City from Prohibition alcohol sales and gambling, made some aspects of the city temporarily depression-proof. The confluence of talent in Kansas City also impacted the makeup of territory bands and the overall style of the jazz they played; soloists took center stage with more frequency and force. Performing groups grew in size, the blues played more of a part in jazz and instrumentation changed with the guitar and bass easing out the banjo and tuba.The Northern Great Plains—as a band travel designation—expanded as far to the east as the border of New York State, if only because territory band activity thinned out as it moved away from the plains proper.

Frank Foster

saxophone1928 - 2011

Count Basie

piano1904 - 1984

In the interview, Foster recalled that "Every gig at that time was a dance. There was no such thing as a jazz concert...the first band that I got with that had actually a name...a local sort of territory band...[was] under the leadership of a man named Jack Jackson, who was a saxophonist. He had this band called Jack Jackson's Jumping Jacks. I played with men who were by far my senior...I was about 14 years of age...We had lots of stock arrangements that were bought in the music store, and a few special arrangements that were made by one or two members of the band. We played for black folks. There were no mixed audiences in those days. You either played for all-black audiences or all-white audiences." Foster recalled several downtown Cincinnati venues that welcomed black territory bands: "There was a place called The Barn. It was a nightclub in downtown Cincinnati. Another place called The Hanger. These were just nightclubs, not dance halls, but just neighborhood bars. Black musicians played there, in trio or quartet format. Black patrons could not go in these places. The black musicians played there." The band members wore dark suits and white shirts as they covered their territory including Southern Ohio, Eastern Indiana and Northern Kentucky where towns were "open," allowing (or, at least, looking the other way) for gambling, drinking and late night/early morning music performances.

Foster described the traveling arrangements as ..."a caravan of cars. We usually traveled in three cars. There was always a black dance in Louisville on [Kentucky] Derby Day, and we worked there. It wasn't life on the road per se. Every trip was there and back in one day, Cincinnati being the home base. We went to Chillicothe, we came back...We went to Louisville and came back. We never went on the road for more than one day. We never went on a trip from which we didn't come back the same evening, so it really was not the road. I think...I made max $10 a job..." "Almost everything that the Basie orchestra became known for...the Jack Jackson band played. Now [in] Northern Kentucky—right across the Ohio River from Cincinnati, are the towns of Covington and Newport. Newport was a wide-open town as far as gambling was concerned. They had after-hour clubs that went from like 1 a.m. to 5 in the morning. I had to get my mother's permission to work a job in this club, the Sportsman's Club, with gambling. I was only 14, 15 years of age. I was placed in the care of an older musician, who promised my mother that he would look out for me and wouldn't let me drink or smoke or anything."

Alphonso Trent

The best of the Southern Plains territory bands, in whole or in part, migrated north in the mid-1920s, ahead of the larger exodus. A highly popular figure on the southwest circuit, pianist Alphonso Trent was a teenager when he began playing with local Arkansas bands. At eighteen, in 1923, he was fronting a band in in Muskogee, Oklahoma and shortly afterward he had moved on to a Dallas-based group which came to be known by his name. In 1925, that city's historic Adolphus Hotel—built in 1912 by beer baron Adolphus Busch—offered Trent an extended engagement; a rarity for a black territory band in the south. Even rarer was that the Dallas radio station WFAA began to regularly feature the Alphonso Trent Orchestra, something that had never been done for a black group.

Jimmie Lunceford

composer / conductor1902 - 1947

Louis Armstrong

trumpet and vocals1901 - 1971

Duke Ellington

piano1899 - 1974

Earl Hines

piano1903 - 1983

It was not unheard of for the more successful territory bands to retain their original home base but expand their geography as their popularity grew. Count Basie and

Andy Kirk

drums1898 - 1992

Charlie Christian

guitar, electric1916 - 1942

The best of the Kansas City-based territory bands were often a jumble of interchangeable players including several who went on to national prominence.

Bennie Moten

composer / conductor1894 - 1935

Walter Page

bass, acoustic1900 - 1957

Count Basie

piano1904 - 1984

Buster Smith

saxophone, alto1904 - 1991

Lester Young

saxophone1909 - 1959

Hot Lips Page

trumpet1908 - 1954

In the early-to-mid 1920s Kansas City based trumpeter Terrence Holder was a regular fixture in that city's territory bands when he formed his own, Dark Clouds of Joy. Holder had earlier played with Alphonso Trent and while his reputation as a musician seemed solid, as a leader he appeared to struggle. His group members decided to replace him in the late 1920s with their saxophonist and tubist, Andy Kirk. Holder spent the next decade working in and around Kansas City with the likes of Buddy Tate, Bud Johnson and Nat Towles but gave up the profession sometime in the 1940s. He went to work as a copper miner in Billings, Montana and was never heard from again. Meanwhile, the new leader had re-christened the group as Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy. Occasionally the group was billed as "The Twelve Clouds of Joy" though it did not have twelve members. Kirk, who had studied under Paul Whiteman's father, kept the band intact into 1948 and at various points in time the group featured

Don Byas

saxophone, tenor1912 - 1972

Howard McGhee

trumpet1918 - 1987

Fats Navarro

trumpet1923 - 1950

Charlie Parker

saxophone, alto1920 - 1955

Hank Jones

piano1918 - 2010

Mary Lou Williams

piano1910 - 1981

Nat Towles' orchestra was widely regarded as one of the best of the territory bands. The New Orleans native was popular from his home town up through Chicago and his group played with a different and powerful pulse that would later be the backbone of swing bands like that of Basie. As Towles moved north he established an early base in Austin, Texas and recruited well-trained students from a music program at Wiley College. In his book (written with Joseph McLaren) I Walked With Giants: The Autobiography of Jimmy Heath (Temple University Press, 2010) the saxophonist refers to a performance with Towles' band at the Prom Ballroom in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Working for Towles at the time, Heath notes that the engagement drew widespread media attention because the venue had not previously welcomed a band of color. It was the booking itself that Heath notes as a significant accomplishment for a black territory band. Towles changed the name of his band to The Nat Towles Dance Orchestra in the 1930s and emphasized swing music. He accepted residencies in a number of locations in and around Omaha, into Chicago, and finally, a date at Harlem's Apollo Theater. His band included trombonist Buster Cooper, who went on to be part of the Apollo's house band, saxophonist Red Holloway, who recorded into the 2000s, Billy Mitchell, who later played with

Dizzy Gillespie

trumpet1917 - 1993

They Covered the Waterfront

Following World War I, excursion boats began adding dance bands to their already burgeoning river tour businesses. Louis Armstrong was among the earliest musicians to take advantage of floating venues and he was followed into the water by performers such as

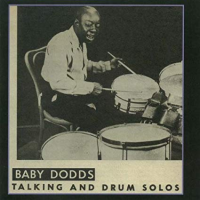

Baby Dodds

drums1894 - 1959

Harry Allen

saxophoneb.1966

Bix Beiderbecke

cornet1903 - 1931

Jimmy Blanton

bass, acoustic1918 - 1942

Pee Wee Russell

clarinet1906 - 1969

Clark Terry

trumpet1920 - 2015

If the Mississippi River had a house band it would have carried the name of

Fate Marable

composer / conductor1890 - 1947

Marable wrote only one original song in his career and recorded just two sides, "Frankie and Johnny" and "Pianoflage" in 1924. Marable was considered a stern bandleader, but one who nurtured young musicians and encouraged them to work toward their strengths. His riverboat band members were expected to play either by memory or ear and from sheet music. Streckfus Steamers included the Dixie Belle where Marable began his career with a group called the Jazz Maniacs. Louis Armstrong had his first river engagement on the same boat. In 1920, Marable had moved to the paddle wheeler, Capitol, now leading a band that included Armstrong, Baby Dodds, and

Johnny St. Cyr

banjo1890 - 1966

Erroll Garner

piano1921 - 1977

Cab Calloway

composer / conductor1907 - 1994

Fats Waller

piano1904 - 1943

Chick Webb

drums1905 - 1939

Play Like a Girl

If a definitive history of territory bands is scarce, the documentation of All-Girl Territory Bands, female leaders, and key players, is exponentially thinner. Jazz, dance music and, for that matter, many types of music performed before a live audience, have been subjugated by men. Female singers aside, women musicians—regardless of their talent—were often used as gimmicks or curiosities in otherwise male-oriented bands. The sexual objectification of women in these bands was a marketing ploy that did little to advance critical reputations of females as musicians, so it is all the more impressive that a number of them had the patience, perseverance and talent to go on to national prominence. As mentioned earlier, Mary Lou Williams was at the forefront of territory band graduates.A native of Atlanta, Williams was a prodigy with perfect pitch who was regularly performing as a pianist while still in grade school. In the mid-1920s, after Andy Kirk replaced Terrence Holder as leader of the re-christened Clouds of Joy, Williams was signed on for various tasks before winning the regular piano role. Williams' contributions expanded as she took on most of the arraigning for Kirk. Kirk's group was considered one of the most popular and durable of all the territory bands -their run lasting more than two decades. They recorded more than fifty sides, mostly with Decca Records but some with the Brunswick label. Kirk was considered an excellent musician but he rarely recorded a solo. His own written account of the territory band years, Twenty Years on Wheels (University of Michigan Press, 1989), is a remembrance, not just of the music, but the realities of being a black, travelling musician where the homes of ordinary people served as a proxy for the shelter and food that establishments did not offer to blacks. Kirk, however, wrote little about the musicians who played for him, and almost nothing about Williams who was generally considered the driving force behind much of the success of the Clouds of Joy.

In her book American Women in Jazz (Wideview Books, 1982), author Sally Placksin writes about the ground-breaking events of Williams career and her impact on the broader music scene. "In 1930 Mary Lou Williams made her historic solo piano recording of 'Night Life,' something she improvised on the spot, unaware that it was even being recorded. With the distinctive Williams touch and colorations, and the strong, propelling left hand, this forthright, joyful piano heralded what the thirties Kansas City 'swing' style would be all about. Within a year of the recording, Williams would become a full-time member of the Kirk band and one of the music's strongest guiding forces." Her accomplishments as an arranger with the Clouds of Joy resulted in Williams sharing compositions and arrangements with

Tommy Dorsey

trombone1905 - 1956

Benny Goodman

clarinet1909 - 1986

Thelonious Monk

piano1917 - 1982

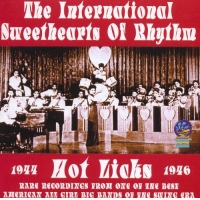

Originally called The Swinging Rays, the

International Sweethearts of Rhythm

band / ensemble / orchestrab.1937

International Sweethearts' saxophonist Rosalind (Roz) Cron joined the group at the age of eighteen and was one of very few white musicians in the band. As the group traveled through the South, the Boston native was stunned by the level of discrimination and hate shown to her bandmates of color. Cron was arrested in El Paso when she attempted to "pass as black," partially in solidarity with those bandmates but also because doing so would avoid the appearance of outlawed integration. In the Judy Chaikin produced documentary The Girls in the Band (Collective Eye, 2011), Cron reacts to the harrowing experiences the band faced while traveling in the South: "During the break I go outside, lean against the rough wood at the back of the building and try to get the shaking in my hands under control. Girl you've got to toughen up, I tell myself. This is only South Carolina—Saine [Helen Saine, baritone and alto saxophonist] says it doesn't get really rough until we hit the deep south. Well, no two-bit sheriffs are going to scare me back to the north. I'll just have to learn what it takes to live with fear and overcome it...Soon we're heading back to the Williams' house for sweet potato pie, milk and a toss of the coin for the bed. Helen and I get the bed; Saine gets the quilt and the floor...the Wiliamses help us walk back to the parked bus with our stuff. We get lots of hugs from Mrs. Williams and a bag of food for each of us. As we climb aboard the bus, she calls, 'Goodbye, Chillun. Yo'all take care of each other and we'll pray to the Good Lord to look after you.' I reach out through the open window, grab Mrs. Williams' hand and say, 'I know how much courage it took for you both to take me into your home and I will never forget you."

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm didn't reach peak popularity until the mid-1940s, rarely recording, and the group dissolved before the end of the decade. They produced a number of musicians who gained notoriety over time, including Anna Mae Winburn, Carline Ray, Tiny Davis, Willie Mae Wong and Violet (Vi) Burnside.

Eddie Durham

guitar1906 - 1987

Coda for the Territory Bands

The beginning of the end for the majority of territory bands was the Great Depression, and at its worst in the early 1930s, many of the groups broke up—some in the midst of engagements where they found themselves unable to even pay for transportation home. There were pockets of the US that still had disposable income for entertainment and cities that did not rely on heavy manufacturing fared better than port towns or steel production centers. Some rural areas that relied on farming, did not feel the effects of the depression as severely as mining towns or cities connected with construction or the auto industry. So, the survivors played their way through the devastated economy and into the 1940s. By that time there were more recent circumstances that finished off the bands: increasingly restrictive union regulations, the popularity of smaller combos and the improving technologies in radio and recording. While some musicians emerged with an elevated status, most were never known at all. For every Jimmie Lunceford,

Illinois Jacquet

saxophone, tenor1922 - 2004

The timeline of jazz—viewed through its various eras—is filled with relatively brief periods of reinvention. The most widely popular era—swing and big band—lasted about fifteen years while bop, cool/West Coast jazz, and hard bop each had peak periods of only about five years. The significance of the territory bands was in their ability and willingness to cast a wide stylistic net; New Orleans, Chicago and Kansas City styles, hot jazz, swing/big band, and gypsy jazz were all part of their repertoire. In the face of obstacles that should have been unthinkable in the US, these bands disseminated music to every corner of the country, often in anonymity.

Related Recordings

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm Hot Licks (Sounds of Yesteryear, 2006)

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm Hot Licks (Sounds of Yesteryear, 2006) The Sweethearts recorded a handful of 78s for Guild Records but they seem to have vanished. Hot Licks is a compilation from radio broadcasts that were recorded near the end of their run, from 1944 to 1946. The sixteen tracks are a mix of standards such as "Sweet Gerogia Brown," "Honeysuckle Rose" and "Tuxedo Junction," as well as some originals. In 2011, the Smithsonian paid tribute to the group and several surviving members, including Roz Cron and Willie Mae Wong were in attendance.

Baby Dodds Talking and Drum Solos (Atavistic, 2000)

Baby Dodds Talking and Drum Solos (Atavistic, 2000) Warren "Baby" Dodds learned to play on a drum that he built himself. He began playing in New Orleans street parades and funeral marches and was later recognized as one of the first jazz drummers to improvise while performing. Dodds played in a number of territory bands but, most notably, spent several years with Fate Marable's riverboat band. Talking and Drum Solos is literally what the title says. Dodds alternates playing drum solos with spoken explanations of his technique, and a bit of history thrown in. The CD is an odd one in that the first eight tracks feature Dodds and the remaining twenty tracks are divided between two rural brass bands with no obvious connection to Dodds. These latter bands are almost comically amateurish and yet there is a charm about their performance that makes for entertaining listening.

Various Artists The Frog Blues & Jazz Annual No. 3 (Frog UK, 2014)

Various Artists The Frog Blues & Jazz Annual No. 3 (Frog UK, 2014) A CD and book combination, the music is culled from historic 78s including one of the two sides recorded by Fate Marable. Marable's Society Syncopaters contribute "Pianoflage" to a twenty-five-track collection that includes Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton & His Red Hot Peppers and blues artists such as Big Bill Broonzy and Poor Boy Lofton.

Tags

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Buy Now

Buy Now