Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer

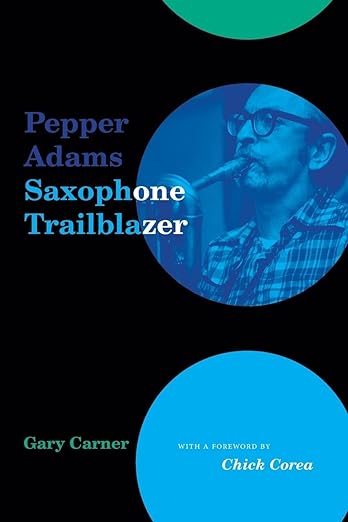

Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer

Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer

Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer Gary Carner

240

ISBN: #9781438494357

Excelsior Editions

2023

Baritone saxophonist

Pepper Adams

saxophone, baritone1930 - 1986

Gary Carner's Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer tells the story of a complicated individual within the context of jazz in America during the mid-to-late twentieth century. The book's origins lie in Carner's extensive interviews with Adams two years before he died in 1985 at the age of 55. In the years following Adams's passing, Carner interviewed approximately 250 of his colleagues and admirers, created the website, produced a box set of "Adams's entire oeuvre" performed by selected artists, as well as an annotated discography before beginning to write the book in earnest in 2017.

In his mid-teens, Adams was already becoming an accomplished tenor saxophonist when he fell in love with the baritone. While

Harry Carney

saxophone, baritone1910 - 1974

Duke Ellington

piano1899 - 1974

Mindful of Carney's accomplishments and inspired by

Charlie Parker

saxophone, alto1920 - 1955

At a time when many others settled for a smaller, tenor-like tone and less-than-complex lines, he succeeded in getting an uncommonly large, full sound and executing complicated figures from the top to the bottom of the horn. "Someone like

Gerry Mulligan

saxophone, baritone1927 - 1996

Bill Perkins

guitar1924 - 2003

Throughout the book, Carner makes a convincing case for Adams's unique approach to the horn and the music. In one particularly astute passage, he identifies Adams's ... "blinding speed, penetrating timbre, immediately identifiable sound, harmonic ingenuity, precise articulation, malleable time feel, dramatic use of dynamics, and utilization of melodic paraphrase." Many of Adams's colleagues weigh in on his strengths. Ray Mosca declares that "Pepper'll make you cry with a ballad." Don Palmer notes that rhythmically speaking, Adams "was as strong as anything I've ever heard."

Gerry Niewood

saxophone1943 - 2009

Hank Jones

piano1918 - 2010

Like many jazz musicians of his era, Adams lived and breathed the music for decades only to receive a smattering of financial rewards and, at best, spotty recognition. Adopting the attitude "that if he played well, better than most anyone else, the world would discover him and reward him accordingly" perhaps wasn't an ideal way to make his mark in a highly competitive field. Adams sometimes lived "a hand-to-mouth existence" but was determined to stay the course. Despite his often precarious economic state, he refused to continue to double on the bass clarinet (which would have opened opportunities for additional studio work), disdained networking and self-promotion, did not seek teaching or Artist-In-Residence positions, and turned down at least one lucrative offer to join the saxophone section of a commercial big band. Also working against him was the perception that his average looks did not make him particularly marketable, the reality that the public "generally favored higher pitch[ed] instruments" over the sound of the baritone, and the complexity of his style demanded an active listener.

Complicating matters even further was his stay of 12 years in the

Thad Jones

trumpet1923 - 1986

Mel Lewis

drums1929 - 1990

At key places in the book, Carner introduces the thorny and complex issue of American race relations relative to jazz, Adams's musicianship, and career. Carner carefully avoids landing firmly on either side of the divide or drawing conclusions. Instead, he introduces a variety of perspectives on Adams as a white jazzman, allows them to bump against one another, and, in doing so, ultimately raises more questions than answers.

Carner makes clear that Adams strongly identified jazz practice with black musicians. In an interview conducted after he moved to New York from Detroit, Adams stated, "I learned how to play jazz from black musicians," and went so far as to assert, "If you want to know how to play jazz, that's how you learn it." In response, Carner asks, "Did Adams alienate himself from the white-controlled network of agents, editors, broadcasters, and promoters by stating his allegiance to black musicians? Perhaps so."

During a decade in Detroit, Adams, accustomed to being the only Caucasian in otherwise black bands, was comfortable playing in venues with virtually an all-black clientele. At the same time, his white peers shunned him because of his large, commanding sound, chord substitutions that sometimes sounded dissonant, and an affinity for material that included songs by Duke Ellington and

Billy Strayhorn

piano1915 - 1967

After his move to New York in the mid-1950s, Adams was one of the "few white members of jazz's black inner circle." Carner quotes an impressive array of black musicians who hold Adams in the highest regard. Some of them believed that, in the words of

Art Taylor

drums1929 - 1995

Carner notes the resentment of jazz musicians on the attention lavished on

Dave Brubeck

piano1920 - 2012

Earl Hines

piano1903 - 1983

Bud Powell

piano1924 - 1966

Erroll Garner

piano1921 - 1977

Thelonious Monk

piano1917 - 1982

Barry Harris

piano1929 - 2021

According to

George Coleman

saxophone, tenorb.1935

The year 2023 saw the publication of first-rate biographies of heavyweights

Sonny Rollins

saxophoneb.1930

Chick Webb

drums1905 - 1939

Henry Threadgill

woodwindsb.1944

Tags

Book Review

David A. Orthmann

Excelsior Editions

Pepper Adams

Harry Carney

duke ellington

Charlie Parker

Gerry Mulligan

Bill Perkins

Gerry Niewood

Hank Jones

Thad Jones

Mel Lewis

Billy Strayhorn

Art Taylor

Dave Brubeck

Earl Hines

Bud Powell

Erroll Garner

Thelonious Monk

Barry Harris

George Coleman

Dick Katz

Sonny Rollins

Chick Webb

Henry Threadgill

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Buy Now

Buy Now