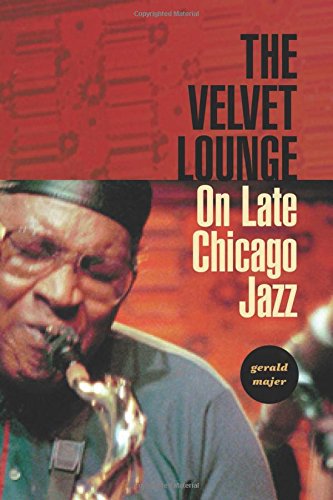

Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » The Velvet Lounge: On Late Chicago Jazz

The Velvet Lounge: On Late Chicago Jazz

The Velvet Lounge: On Late Chicago Jazz

The Velvet Lounge: On Late Chicago Jazz Gerald Majer

224 pages

ISBN: #023113682X

Columbia University Press

2005

Three men sit around a table in a restaurant that—for one night a week—masquerades as a jazz club. The dinner plates have been cleared, and we're waiting to settle the check. On the other side of a divider, the musicians are getting ready for the night's opening set. The service is slow so there's time to kill before we move into the part of the room where the music will play and finally get down to the real business of the evening. We catch glimpses of and greet some of the performers, most of whom have been encountered in the past, live and on recordings. Each of us is wondering what this particular ad hoc combination of personalities will sound like.

The heady buzz of anticipation has stalled temporarily while we continue to wait. Between the three of us, there's roughly one hundred and fifty years willingly spent in bars, clubs, concert halls, and venues of all shapes and sizes. (A couple of years ago one of us caught two sets at a Sunday morning flea market). The talk turns to whom, where, and when—the details of stories that diehard jazz fans inevitably trot out when there's some downtime. Our personal experiences as listeners and witnesses to jazz history overlap to some degree, yet, in part, it's the differences in perspective that make the conversation something more than, as one wag once put it, "You boys just swapping jazz baseball cards."

A recurring theme is long shuttered jazz clubs—Gulliver's, The Three Sisters, Boomers, The Jazz Forum, Slug's Saloon, The Half Note, just to name a few—all of them an integral part of who we are as jazz aficionados. Because we're in our sixties and seventies, the names attached to some of our cherished memories are becoming elusive. A hint—the name of a professional associate, a record date, or any other kind of minutia—is enough for someone at the table to hit on the name. (It helps to have like-minded friends.) Then, of course, there are the unforgettable performances, the impact and importance of which can't always be communicated to the teller's satisfaction. (You really had to have been there.) Lastly, there are the things we're done (and, perhaps, risked) for the privilege of witnessing peak experiences. As two of our wives sit and converse about other matters (they've been in this loop many times before and heard some of the stories more than once), one of us talks about falling asleep at work under a vehicle he was repairing, the result of a number of consecutive late nights of catching sets by an artist who couldn't be missed.

I discovered Gerald Majer's The Velvet Lounge: On Late Chicago Jazz shortly after its publication in 2005. Like the jazz recordings I return to time and time again, and the memories of live sets I often summon for inspiration, it never completely leaves my consciousness, exerting a profound influence—a broadening effect, a vista of possibilities—in the manner I look at the music and my experiences with it. Reading Majer is, at once, exhilarating, enlightening, disarming, and frustrating. At his best, Majer's writing induces the elation that one feels on those great nights when the artists can do no wrong, and the music stays with you long after the performance is over. When he offers points of view or impressions of particular artists—brief sketches of

Wayne Shorter

saxophone1933 - 2023

Andrew Hill

piano1931 - 2007

Roscoe Mitchell

saxophoneb.1940

Majer isn't a jazz historian, music scholar, or critic. He weaves aspects of these roles into the book, but his primary relationship to the music exists in conjunction with autobiographical sketches, floods of vivid imagery, speculation, imaginative leaps, literary references and, most of all, a wide-ranging interest in the natural world (parks and trees figure prominently in some of the essays) and the structures and systems that humankind imposes on it. In short, it's impossible—indeed, undesirable—to separate Majer's life, times, catholic interests and obsessions from his love of jazz. The book is unlike other jazz-related texts in that it doesn't leave you with a lot useful facts, isn't subject to glib interpretation, and doesn't have a uniform or easily recognizable perspective. Majer's complex, highly subjective account of his entanglement with the sounds of jazz makes my pre-performance conversations with friends seem quaint, as if from a distant era when things were much easier to explain and put in order.

At times Majer is not unlike an individual often encountered at various jazz events: The kinetic, wild-eyed, (usually) young man, transported by the music to a personal space, oblivious to all other realities. However, in Majer's case, sometimes the music-induced state of ecstasy is not simple and altogether pleasurable. In a passage about Roscoe Mitchell, he writes of "a music of rigorous invention at the same time so dazzlingly eccentric and exorbitant I despair of writing another word about it, only feeling an impolitic desire to shout, to roll on the floor...not because I'm being affirmed, the music giving me what I want, but because it's messing me up, it's taking me apart, it's a plaguing where I'm stalled and tranced in a rawly prepositional element, a wild territory of suspended objects, crisscrossed paths, vanishing trails." (p. 180)

Majer was introduced to jazz as a teenager at a used bookstore in Chicago he often frequented, where the cabdriver/proprietor continuously spun records and occasionally talked about himself. A brief outline of the circumstances of the arrest of tenor saxophonist

Gene Ammons

saxophone, tenor1925 - 1974

After concluding his version of the story of Ammons' arrest and adding more speculative material about the tenor saxophonist's experience in prison, Majer shifts to a night many years later, when he witnessed his idol perform at a club. He captures the unconscious sense of privilege, the voyeuristic detachment, as well as the weight of expectations that fans put on their heroes while in their immediate proximity. "I could watch him at my ease because he had nothing to do with me, he operated in the near yet ideal world of the music, the instrument, the intimidating superiority of his name and his art. That night, however, I felt myself drawing uncomfortably close, his gaze catching now and then on mine as though he felt its pressure, maybe resented the way I was sitting there gobbling him up, unseemly in the controlled swoon of the cognoscenti's delight." (p. 11)

In a chapter entitled "Stitt's Time," Majer posits alto/tenor saxophonist

Sonny Stitt

saxophone1924 - 1982

In addition to describing Stitt's artistic self-mechanization, speculating on his relationship to

Charlie Parker

saxophone, alto1920 - 1955

Despite the overwhelming desire to reach end of shift and pursue satisfactions outside of the workplace, Majer and his peers on the line couldn't resist executing mini-rebellions to slow down the pace of production and force management to extend the workday into overtime. ..."if each of us slacked off a little bit—a slight languor in the arm, a screw dropping to the floor instead of being driven home, maybe trouble with the drill again, who could tell—it wasn't easy for them to identify a point of resistance, and if they did it wouldn't matter, because the point was moving, at the same time everywhere and nowhere." (p. 18-19)

The primal urge to pound something, to constantly strike an object or person as a means of bringing order or chaos, looms large over a chapter entitled "Batterie." Though Majer imaginatively writes about jazz drumming as practiced by

Elvin Jones

drums1927 - 2004

Famoudou Don Moye

drumsb.1946

Ed Blackwell

drums1929 - 1992

Reminiscent of Majer's close encounter with Ammons, we're treated to a front row seat to experience Elvin's drumming—exhilarating and exhausting, something the author experiences with his body, mind, and soul—but there's nowhere to hide, no way to detach oneself from the author's descriptions of dodging and bearing the brunt of blows of a gauntlet his childhood friends called the punching machine. ..."the tighter grouping, the circle, was serious business. Face to face, the guys going at you fed off one another. There was no exit until you dropped in surrender to the ground and begged for mercy, or you did the near impossible: beat your way out...You knew the simplicity and the dumb justice of being a target." (p. 95) On the next page, in describing a live performance, Majer makes a daring, figurative connection between interpersonal violence and blows struck to inanimate objects in the name of art: ..."Elvin Jones beating the daylights out of me, black stars and silver asterisks, a sun-spiked bedazzlement—he threw the first punch, the others, all." (p. 96)

Analogous to listening to and pondering the sounds of jazz for decades, several encounters with The Velvet Lounge have left me with a great deal to think about, as well as a certainty that there's more to be discovered. Recently, a friend was describing his shifting regard for the music of

Lester Young

saxophone1909 - 1959

The Velvet Lounge: On Late Chicago Jazz

Gerald Majer

211 Pages

ISBN: #0-231-13682-X

{{e: Columbia University Press}

2005 .

Tags

Fred Anderson

Book Reviews

David A. Orthmann

Wayne Shorter

Andrew Hill

Roscoe Mitchell

Gene Ammons

Sonny Stitt

Charlie Parker

Elvin Jones

Famoudou Don Moye

Ed Blackwell

Lester Young

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Buy Now

Buy Now