Home » Jazz Articles » From Far and Wide » Travelling the °∞Rhythm Road°±: Jazz Ambassadorship in the...

Travelling the °∞Rhythm Road°±: Jazz Ambassadorship in the Twenty-First Century

Count Basie

piano1904 - 1984

The Rhythm Road: Devin Phillips in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Dec 2007

The Rhythm Road: Devin Phillips in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Dec 2007 Chapter Index

- Roots of The Rhythm Road

- Travelling with the Rhythm Road Musicians

- Dangers Along the Road

- Encounters between American and Local Music and Musicians

- Running the Show

- Bringing it All Home

- Travelling with the Rhythm Road Musicians

Roots of The Rhythm Road

The roots of this innovative program go back to the very origins of jazz. From its inception, jazz has depended on links between America and the people of other nations. Its sources are international, having originated in New Orleans, a multi-ethnic harbor city of boat crews, workers, immigrants, travelers, and entertainers. Then, in the Jazz Age and the Modern Jazz era, the music traversed the Atlantic and became popular in Europe, with our musicians frequently performing and mentoring there. Moreover, African American musicians were made to feel more at home on the Continent than in their then segregated country, and often took up residency. Jazz became a major avenue for Europeans to learn about American culture, providing a more intimate glimpse of our people than the media and complementing the presence of American tourists, expatriates, and soldiers. Soon, the reach of jazz extended to Japan and other parts of Asia, and later to Africa, the Middle East, and South America. Paradoxically, today jazz is more popular in many of these countries than in the U.S.

Around the world, jazz came to represent the American ideals of individuality, romance, and freedom, whether in nations that were enemies or allies. Bandleader and composer

Chris Walden

arranger

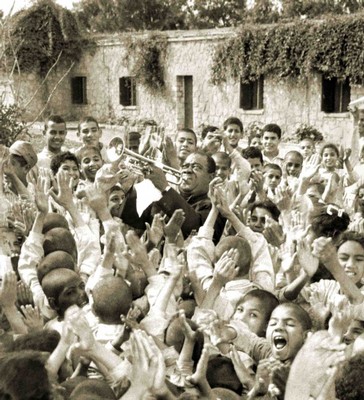

During the Cold War, beginning in 1955, the Congressional Representative from Harlem, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. initiated a government-sponsored set of globe-trotting jazz in the form of the well-known Jazz Ambassadors Program of the U.S. Department of State. The project, which was later assisted by promoter George Wein, sponsored international tours that included such luminaries as

Dizzy Gillespie

trumpet1917 - 1993

Louis Armstrong

trumpet and vocals1901 - 1971

Duke Ellington

piano1899 - 1974

Ella Fitzgerald

vocals1917 - 1996

Dave Brubeck

piano1920 - 2012

Recently, in 2005, the U.S. State Department Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs reconfigured the musical ambassador idea in cooperation with Jazz at Lincoln Center (J.A.L.C.), where

Wynton Marsalis

trumpetb.1961

Travelling with The Rhythm Road Musicans

The bare-boned facts about The Rhythm Road, however, leave out the color and the "feeling of what happens." All About Jazz wanted to know the inside story, what actually occurs on these tours, what the real life experience is like, and what it really accomplishes. To get a bead on this, AAJ contacted the program's touring director, Susan John, who is involved in all aspects of planning and implementing The Rhythm Road itineraries. She often travels with the musicians and offered a snapshot of one tour, which took the group in and out of the population centers, giving the flavor of the experience: "In Zimbabwe we were in a school setting. A forty-five minute drive through a somewhat barren area with a few concrete buildings, and then you couldn't even tell it was a classroom building. In the course of ten minutes, it went from an empty building to sixty or seventy kids packed in waiting for us to do something, anything! Contrast that with our evening performance a day or two before in a crowded festival setting with many patrons convening for a week-long festival of artists from all over the world, and they looked forward to this jazz quartet. So it ranges from small to large, informal to formal. And one of the purposes of the program is cultural exchange, and you see just as much dialogue after the concert, when a musician is packing up the drums, and he's flanked by six people, drummers and others, and you're just seeing the connections that can happen on all levels." The combination of music and informal conversation is the basis of the diplomatic "magic" of The Rhythm Road.

In the cities, there are major concert performances, as well as gatherings at the embassies of the host countries. Trumpeter

Charlie Porter

trumpetb.1978

Adam Birnbaum

pianoIn addition to the music, the face-to-face interactions between musicians and audiences leave lasting impressions that can have a direct impact on relations between different countries or segments of society. Drummer Tim Horner, whose group, the Mark Sherman/Tim Horner Quartet (pictured below left), with

Jim Ridl

piano

Roseanna Vitro

vocalsb.1954

Says Porter, "The program involves embassy representatives from the host country. They not only want us to play at the embassies, but also in the local communities to build a cultural bridge. Jazz is a great vehicle for diplomacy because it embodies the true spirit of democracy, and it also gives the locals a holistic view of the culture of America, since jazz is so much a part of our country." Susan John feels that the music itself has a transformative impact: "You see the overall power of music. What comes to mind is that when I was in Mexico with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra (this trip was independent of The Rhythm Road program), and the flood of emails and phone calls that came in saying 'That was the greatest concert of my life.' The director of the modern art museum, who had sworn that he couldn't stand jazz, said 'I completely changed my mind.' The recurrent theme is transformation. What that says for how Rhythm Road influences perceptions of America, I can't completely say, but I do know that the good will engendered is immeasurable, and whether that translates to 'I didn't like America before, but now I do' I can't say, but I do think the person-to-person and musical good vibes that we leave them with has a positive effect."

Dangers Along the Road

Sometimes, the musicians visit countries where war and other calamities pose an ever-present threat, even to the musicians themselves. Horner recalls that, on a prior non-Rhythm Road journey in Kyrgyzstan, the group was held up at gunpoint by the police. "The language barrier complicated things, and it was scary. We were afraid we would be arrested or even shot." In adjacent Tjikistan, "with all the political unrest, it was so intimidating, who knows if anyone will go back there again any time soon." Then, "when we drove around Bosnia it was beautiful, but the Embassy told us there were land mines all around." But even in such tense situations, mutual discussion and correction of misconceptions can occur. Says, Horner, "When we were in Belgrade, we witnessed many of the buildings that had been blown up by the U.S. Air Force when Clinton was in office, trying to stop Milosevic from invading Bosnia. We had some interesting political discussions. Some of the people didn't know why the U.S. 'invaded' their country. You realize how important the media and the press is for the knowledge of the public. A lot of people weren't aware of the whole story. They just thought we invaded them for no reason."

But encounters with danger are the exception rather than the rule. Many places, though poor or undeveloped, are safe for travel, and part of the responsibility of the host emabassies is to facilitate the musicians' comfort and safety. Horner's memories of touring Paraguay, Colombia, Uruguay, Ecuador, and Chile with Roseanna Vitro were not of danger but of the music, the awesome mountain scenery, and the warmth of the local people.

The Rhythm Road: Dana Leong in Vietnam, Dec 2007

The Rhythm Road: Dana Leong in Vietnam, Dec 2007 Encounters between American and Local Music and Musicians

Perhaps what is unique about The Rhythm Road form of diplomacy are the experiences and exchanges that occur between the American and local music and musicians. To begin with, the tour bands encounter musical instruments and styles they're not familiar with. Porter notes: "In some countries, they may not even have pianos—that instrument doesn't exist in some places! Some countries don't have drum sets. In Africa, as you can imagine, they all had drums. But a typical jazz drum set is nowhere to be found. But one of the exciting things in Africa is that we'd always have some amazing drummers come out. And our drummer, Quincy Davis, was able to learn so much from them." So, if you hear a jazz musician use an unusual instrument, it's possible he found it on a Rhythm Road or similar expedition! Saxophonist

Dave Liebman

saxophoneb.1946

Sometimes though, the differences in instrumentation can be daunting. Horner tells us that "New York drummers are into the open sound of the drums, but when you travel, as in Germany, the bass drum actually has a hole in the front for the microphone and is stuffed with laundry and pillows, because that's their idea of what a bass drum sounds like—they don't understand the open tone. But it's a good challenge to go up and not play your instrument and make something happen." The point is that the need to adapt often results in learning and creativity. After all, jazz itself is about improvising!

Even more challenging can be the differences in the music itself. At some of the concerts, local musicians are welcome to come up and jam. Says Horner, "Sometimes we play with guys from the local area. They play very differently from us. Like one guy played the clarinet, and even the structure of the bar was different than ours. He couldn't play in 4/4! We made it through the blues somehow. Swingin' in four is not part of his culture. And these people play fast, and the people get up and dance, and we had a hard time following their rhythms!" (Think of Dave Brubeck's famous "Take Five," in 5/4 time, and you realize how much 4/4 is instilled in Western ears, making that tune a breakthrough!) The musicians' ears are stretched by these multicultural jam sessions, which play an increasingly important role in the development of jazz in the "global village."

Musical as well as cultural and diplomatic exchange is thus facilitated by the Rhythm Road. As Porter points out, "Jazz is a 'sponge.' You soak up things from all cultures. For example, in West Africa they have this thing called the kakuzi rhythm. Or another country might have a scale you've never heard before. And you can incorporate all that stuff into your music. And jazz has always been that way. You mix that with Western influences, and you get something new. That's why jazz is great diplomacy: it breaks those boundaries. It's a great vehicle for people to improvise, and to participate you don't even necessarily have to speak the same language. And the language of jazz itself is always growing through these new influences."

Running the Show

Behind the scenes of these experiences are the logistics and administration of The Rhythm Road, the engines that make it all happen. For one thing, for such a program to succeed, the musicians need to be selected not only in terms of their musical approach and ability but also their personal stamina for travel and their ability to communicate and interact with folks of diverse languages and cultures. The Rhythm Road musicians must also be good diplomats. Susan John described the selection process as follows: "Each year we have a panel of judges which does not include Rhythm Road or State Department staff. For this panel, we like to choose among musician educators who can assess the candidates in terms of both their music and their capabilities as educators. For example, at the end of October, 2009, we convened a panel of Damian Smeed, who is a gospel musician with experience in other genres;

Don Braden

saxophone, tenorb.1963

The Lincoln Center and Jazz at Lincoln Center Artistic Director Wynton Marsalis in particular are crucial to the progam's inner working. Says John, "Part of the Jazz at Lincoln Center (JALC) mandate is to bring jazz internationally to the world. Lincoln Center has twelve individual constituents such as the Metropolitan Opera, the NYC Ballet, the Juilliard School, and so on, and JALC is one of those independent entities that fall under the Lincoln Center umbrella. In 1987, we were a series of summer concerts. In 1992 we became a department of Lincoln Center, and in 1996, we were granted full-fledged constituency." The connection of The Rhythm Road to Lincoln Center, with the latter's incredible concentration of musical and performing arts forces, provides a context that allows The Rhythm Road to thrive. The multifaceted performance context fosters a rich understanding of music as an art form that incorporates diverse formats and cultures and is based on both tradition and innovation.

Susan John thinks that Wynton Marsalis deserves major credit for the success of Rhythm Road. "He's involved in everything we decide to do. Regarding Rhythm Road, he was involved in the original liason with it, and also in every aspect since then. When we looked to program expansion, he was at the table when we talked about additional genres such as zydeco and gospel as to how to best showcase American music. He was also a judge on the selection committee two years ago. He was involved philosophically, but now our concerns are more structural, so he's less involved with that. And he doesn't go on the tours themselves." Nonetheless, musician Horner believes that Marsalis has had a very positive influence on the project. "He follows everything that's going on. He had a lot to do with our teaching and master classes. Wynton said to us, 'As you're out there travelling in other countries, and people strike up political conversations, don't apologize for America, talk about the music.' Wynton was right. This is not about the politics but about the music and the people who are out there livin' the life."

As accomplished as Marsalis has proved himself in so many arenas, he is a controversial figure to many jazz artists, who feel that his musical conservatism (at times he seems to have ignored advances in jazz beyond New Orleans and Duke Ellington) combined with his fame and influence have held jazz back. Horner thinks he may have changed in that respect. He remembers a recording date they did where Marsalis opened up to him. "We were working on a recording put together by

Ted Nash

saxophoneb.1960

Bringing it All Home

Finally, the "back at the ranch" question comes up. What, if any, manifestations of The Rhythm Road occur stateside? For one thing, Rhythm Road musicians perform free concerts in the United States. Jazz at Lincoln Center hosts the ensembles at Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola and at Frederick P. Rose Hall, its New York City home. In Washington, D.C., the concerts are presented by National Geographic Live! at the Grosvenor Auditorium.

In addition, there is considerable debriefing and discussion on home turf. Meetings are held where all the administrators and musicians get together to share experiences and talk about what worked and didn't work. Says John, "We're always focusing on how to make what we do better. How best to make an impact in those countries is our emphasis. We work on developing our educational sessions. We get four mentors who have been on the Rhythm Road tours in the past, and when the musicians are better equipped in this way, they can make more of an impact during their travels. The breadth of locations and music is already built into the program, so the focus is how to insure quality at every turn."

In conversation with AAJ, Tim Horner offered a suggestion which could add something valuable to The Rhythm Road mission. "I've asked them to consider doing a week-and-a-half tour of all the musicians to places in America. We'll show America what we're doing and what their tax dollars are doing." A "show and tell" demo of the program to the "tax-payers" could help perpetuate and expand The Rhythm Road abroad and encourage similar ventures. But above and beyond that, America has its own "underdeveloped" and poverty stricken rural areas and urban ghettos that desperately need the warmth and inspiration that these musicians can bring them. Moreover, jazz itself is crying for a renaissance in the U.S. So why not have a domestic version of The Rhythm Road? For this component, the State Department, which handles foreign affairs, could transfer part of the reigns to some other government agency and local communities. It would be a way to bring the varied rewards and insights of The Rhythm Road home to our own people. In addition, as part of such a domestic version of "The Rhythm Road," musicians from other countries could be brought here to play for us Americans. As the saying goes, "What goes around, comes around."

Photo Credits

Page 1: Jazz at Lincoln Center

Page 1: Louis Armstrong Archive

Pages 2: Jazz at Lincoln Center

Tags

General Articles

Victor L. Schermer

United States

Count Basie

Chris Walden

Dizzy Gillespie

Louis Armstrong

duke ellington

Ella Fitzgerald

Dave Brubeck

wynton marsalis

Charlie Porter

Adam Birnbaum

Jim Ridl

Roseanna Vitro

Dave Liebman

Don Braden

Ted Nash

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Buy Now

Buy Now