Home » Jazz Articles » The Jazz Life » Getting Past (E)Go

Getting Past (E)Go

Every time I hear myself on tape after a gig I want to cringe and cry at the same time, despite people making nice comments about my playing (What kind of tin ears do these people have, anyway?). I force myself to swallow that indigestibly familiar feeling. I give it a few days for my traumatized ego to quieten, for my dose of humility to kick in, and then I remind myself what Berns told me in essence, that it's not my job as a musician to be fabulous or brilliant or any other egocentric thing. Just play the tune well.

Nevertheless, I still hung out with friends, a number of whom are recognized great players, and when one of them asked me how I could keep a guitar and not play it very much knowing how much I had practiced every day for years, my response was, "It's not a great idea to keep dating your ex-wife."

I continued to have what I might call a number of musical one-night stands, hanging and playing with friends, jamming along, keeping my head above water, being part of the scene if to the side of it somewhat with recording musicians. I was free of the pressure to keep up, though, as I saw it. (Of course, I'm the one who put that pressure on myself.) I had fun in the moment and could rise to the moment in the company of these guys. My friends were willing to play with me, and I managed to keep my chops just this side of rusty as a result.

I started practicing again because of my son. When he was six we took him to a music exploration day at the Bloomingdale School for Music and he spent all afternoon running up and down stairs blowing on this thing, plucking that thing, whomping on something bangable, but he kept coming back to the violin and the teacher. We got the message. He wanted to be a violinist. After we arranged for him to take lessons at Opus 118, which was in the heart of Harlem at the time, I started practicing again because I thought it would be a good idea to give him a model of someone who practices an instrument as something usual, not something unusual and exotic. I became the anti-dad. "You can give this up any time you want," I would tell him. "No, no, no, no, no," my young son would say, his chin jutting out defiantly. "Then you have to practice," I told him calmly. "You can't half do this." And I found it was contagious. I was enjoying practicing and playing again, and so, little by little I got into the routine of studying and practicing and playing once again. Over the years I've met and played with loads of musicians and one of the few negative things we all have in common is a sometimes strong dissatisfaction with our own playing.

After I started studying again, I told

Peter Bernstein

guitarb.1967

Every time I hear myself on tape after a gig I want to cringe and cry at the same time, despite people making nice comments about my playing (What kind of tin ears do these people have, anyway?). I force myself to swallow that indigestibly familiar feeling. I give it a few days for my traumatized ego to quieten, for my dose of humility to kick in, and then I remind myself what Berns told me in essence, that it's not my job as a musician to be fabulous or brilliant or any other egocentric thing. Just play the tune well. Improvisation is essentially embellishment of the tune. So whenever I get into my "Oh my God, how can I sound like that," mode, I essentially wait it out and then go back to that (current) infamous recording thinking, "OK let's start defining what it is that really horrifies me so. Because THAT is what I need to work on next. Do more of THAT, and try not to do as much of this other thing." Very often it involves forcing myself to vocalize what I'm doing during my practice sessions. For some reason I find this a continuing struggle to do well, forcing the fingers to obey the brain, not the other way about, because otherwise the instrument becomes the master, rather than the tool.

My job as a musician is simple—find ways to creatively define a song's harmonic and melodic possibilities when I improvise, and to just play the damn tune properly. (Hit the ball in the middle of the racquet, damnit!) And along with mastering rhythmic possibilities, for me that's enough. My first serious music teacher, in England where I grew up, was the bassist

Peter Ind

bass, acoustic1928 - 2021

Lennie Tristano

piano1919 - 1978

Ray Brown

bass, acoustic1926 - 2002

Oscar Pettiford

bass1922 - 1960

Peter told me a story of a new student of his, a professional trumpet player who wanted to "buff up" his jazz playing. After several weeks of lessons the trumpet player quit, telling Peter that far from making him a better player, Peter had made him play worse! Peter's point to me, and I knew it to be true because he was (and still is) one of the best teachers I've ever had, was that far from making the guy play worse, he had managed in a few short weeks to open up his ears, and the guy, perhaps for the first time, was able to hear what he actually played like. It was a shock to the system. The next step, the one the guy was not able to take, was to shuck the ego and listen to his playing as if he was teaching another musician not himself.

Another great influence on me is the remarkable west coast player

Larry Koonse

guitar, electricThat led us to a discussion about perfectionism, and how debilitating it can be, and how it hit him so hard after he graduated music school (Larry was the first recipient of a Bachelor of Music in Jazz Studies at the University of Southern California), that he stopped playing for months before finally starting up again, a little bit each day at first.

Chick Corea

piano1941 - 2021

Find a player whose playing you connect to and love, and play along with it as best you can. Try and mimic the flow and the rhythms. Record yourself playing something. (The great English jazz guitarist

Dave Cliff

b.1944Finally, there's what Chick calls the "Apprentice System." Find a Master to work with, someone who has an ability you'd like to have, and go make music with them. This is how we learn a skill. Work with people that you want to learn from and who can help you figure it out.

At its best, music is something outside of us, an energy stream that we strive to somehow plug into using our ears and our fingers, like launching out on a plank without a life jacket into a fast moving river. It's something that we manage, through the meditation of practice, to connect with when we are on the stand. We become conduits for something "other" that passes through us, and is shaped as it enters the world by who we are at that moment. Our job is to simply get out of the way and let it flow through.

Hit the ball in the middle of the racquet. Not so easy, is it?

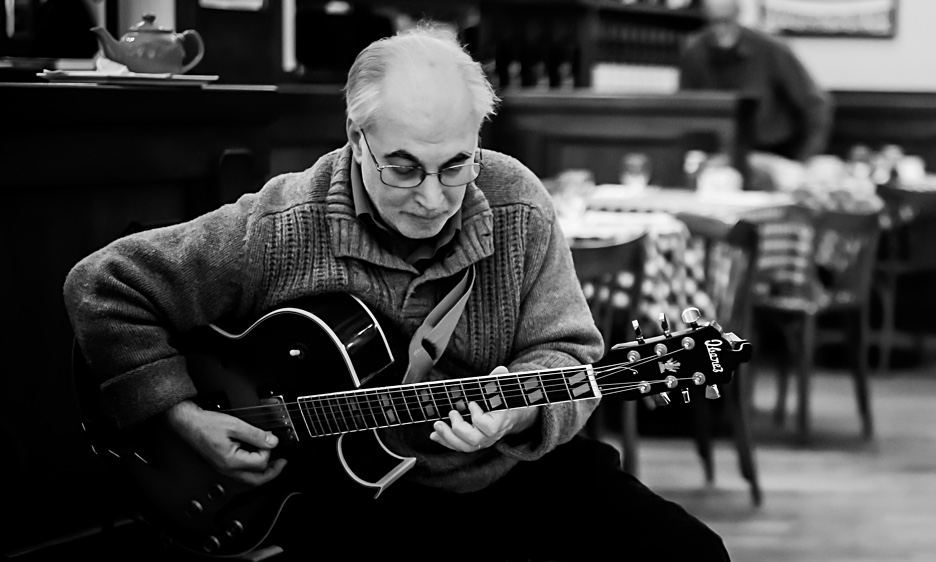

Photo credit: Jordan Witfield(

Tags

The Jazz Life

Peter Rubie

Peter Bernstein

Lionel Hampton's

Charles Mingus

Peter Ind

Lennie Tristano

Ray Brown

Oscar Pettiford

Larry Koonse

Chick Corea

Dave Cliff

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Buy Now

Buy Now