Home » Jazz Articles » Under the Radar » Jazz Education: The Next Generation, Part 1

Jazz Education: The Next Generation, Part 1

How can one justify the serious discussion on the college level, of a subject whichАГmakes an art out of vulgarity?

—Harry Allen Feldman

Ken Prouty, an assistant professor of Musicology and Jazz Studies at Michigan State University and author of Knowing Jazz: Community, Pedagogy, and Canon in the Information Age (University Press of Mississippi, 2013) has written at length about the early history of jazz education in the US. In his writings, he has pointed to the period from the advent of U.S. jazz and into the 1940s, as one where written records regarding formal jazz training was negligible.

Prouty accentuates that "Even into the 1960s, as jazz was becoming more accepted in society at large, many in the academy would employ this same kind of rhetoric in justifying the exclusion of jazz from the curriculum. As [music educator] Harry Allen Feldman writes... 'who can deny the close relationship between jazz and delinquency... how can one justify the serious discussion on the college level, of a subject which...makes an art out of vulgarity?'" Feldman, like others in the larger music world at that time, was a classical elitist with a somewhat hysterical view of jazz.

More than most academic disciplines, the concept of being self-taught was seen as beneficial and/or essential among the jazz musician population, while being either scorned or ignored in the academic world. Whatever the case, for most jazz musicians, economic, geographic or other accessibility issues, made an academic path a less likely option in the first decades of jazz in the U.S. Near the end of the 1940s jazz curriculums had been instituted in what was later to become the University of North Texas and Boston's Schillinger House, later renamed as Berklee. These were exceptions and it wasn't until the 1960s and 1970s, that the U.S. saw sizable development in college and university jazz programs.

There were, of course, alternatives to a purely jazz-oriented education. In the early days of modern jazz, school band programs, correspondence courses and technical high schools filled a void in jazz education. In 1911

Louis Armstrong

trumpet and vocals1901 - 1971

Bix Beiderbecke

cornet1903 - 1931

Chet Baker

trumpet and vocals1929 - 1988

Miles Davis

trumpet1926 - 1991

Henry Threadgill

woodwindsb.1944

Benny Carter

saxophone, alto1907 - 2003

Muhal Richard Abrams

piano1930 - 2017

In remote rural areas and/or socio-economically challenged parts of the country, the choices for formal music education were even more limited. Beginning in the 1920s, territory bands were mid-sized ensembles that staked out particular geographic areas, bringing a mix of dance and big band jazz to venues like VFW halls and Elks lodges. Typically consisting of up to a dozen musicians, these groups would book anywhere from one night to a week in a town and move on to be replaced by another territory band. But in the most inaccessible areas of the country, this was not an ideal option. Lack of access and appropriate venues were countered by a proliferation of radios playing big band jazz, and communities that sorely wanted that form of recreation as a respite from six-day work weeks filled with natural dangers. In the book Big Band Jazz in Black West Virginia, 1930-1942 author Christopher Wilkinson relates the story of coal mining towns throughout that State's panhandle. Though poor by pre-Great Depression standards, these towns were relatively well-off in comparison to even bigger cities during the worst of the economic collapse. They had the means and the willingness to patronize the musicians if not the logistics to host them.

The solution came in the form of West Virginia's college bands. With names like The Campus Nighthawks, the Dixie Blue Devils and Chappie Willet's Campus Revelers, these school organizations took an erudite and thoughtful approach to their training of musicians and to producing the highest quality in performances. Often recruiting formally educated conductors and arrangers, even from local high schools, these bands began to emerge, playing in schools, churches and outdoors. For all involved parties, the dedication to learning the music and mastering instrumentation was tenacious and it became the centerpiece of social life in these communities. With few outlets for publicity they relied on word-of-mouth and handouts and drew large groups. The school bands were so popular in the mining communities that they transcended the segregation that was entrenched in local housing, bringing the black and European immigrant communities together.

Formal music education in Europe and parts of Asia had been widely implemented long before the United States added such programs and those U.S. programs did not typically reflect popular music trends or hands-on instrumental instruction. There were exceptions. Notably, the predominantly black Tuskegee University, founded in 1881 by Booker T. Washington. Among the many famous alumni of the school was

Teddy Wilson

piano1912 - 1986

Billie Holiday

vocals1915 - 1959

Benny Goodman

clarinet1909 - 1986

Gene Krupa

drums1909 - 1973

Ella Fitzgerald

vocals1917 - 1996

Marian McPartland

piano1918 - 2013

By the 1960s there were more than two-dozen colleges that featured jazz bands and the number grew exponentially through the decade. A benchmark in the growth of college jazz programs came with the introduction of the

Stan Kenton

piano1911 - 1979

Woody Herman

band / ensemble / orchestra1913 - 1987

Stan Getz

saxophone, tenor1927 - 1991

Dizzy Gillespie

trumpet1917 - 1993

Bob Belden

arrangerb.1956

Woody Shaw

trumpet1944 - 1989

A later—but prominent—addition to the jazz camp scene is the Litchfield Jazz Camp, founded in 1997 at the Canterbury School in New Milford, Connecticut. Saxophonist

Don Braden

saxophone, tenorb.1963

Mario Pavone

bass1940 - 2021

Peter Madsen

pianob.1955

Andy McKee

guitarb.1953

Gerald Cleaver

drumsb.1963

The proliferation of jazz camps has led to similar projects in Europe. The Sligo Jazz Project, in its namesake town on the northwest coast of Ireland, is one of the best known. It consistently attracts top talent to its faculty and is unique in providing a substantial number of opportunities for students to hear professional international performances. Among those who have performed in the past are

Kenny Wheeler

flugelhorn1930 - 2014

John Taylor

piano1942 - 2015

Zakir Hussain

tablas1951 - 2024

Rufus Reid

bass, acousticb.1944

Gwilym Simcock

pianob.1981

Adam Nussbaum

drumsb.1955

Steve Rodby

bass, acousticb.1954

From the 1940s to the 1980s, the growth of college jazz programs was slow-growing and tended to be in population centers away from the heartland. The Jazz Institute of Chicago began promoting jazz education in 1969 through that city's secondary schools. The California Jazz Conservatory was founded in 1997, but not accredited as a conservatory until 2014. But—not surprisingly—development moved faster in the New York and Los Angeles areas. The New School in Manhattan offered its first jazz history course in 1941 (taught by Leonard Feather) and years later established a complete program to mentor working New York-based jazz professionals. In 1964, Manhattanville College, just north of NYC, became the first school to offer a graduate degree program in music education. In 1972, William Paterson University began a jazz program directed by

Thad Jones

trumpet1923 - 1986

Herbie Hancock

pianob.1940

Wayne Shorter

saxophone1933 - 2023

In the second part of Jazz Education: The Next Generation the focus will be on two schools that have made jazz education a cornerstone of their institutions. The State University of New York, Purchase College, and Toronto's Humber College are taking responsibility not just for music education but also for preparing students for managing their careers in a profession that has left many destitute when they could no longer perform.

Recorded for radio broadcast, the setting of Marian McPartland's long-running National Public Radio series allowed for an unusually intimate look at Teddy Wilson. More often than not, he played and recorded in big band formats. In this solo and duo situation, Wilson—now late in his career—plays with the same sense of swing that he owned in the 1940s. Without being filtered through orchestration, the emotion in Wilson's playing is stronger but, as always, without sentimentality.

Recorded for radio broadcast, the setting of Marian McPartland's long-running National Public Radio series allowed for an unusually intimate look at Teddy Wilson. More often than not, he played and recorded in big band formats. In this solo and duo situation, Wilson—now late in his career—plays with the same sense of swing that he owned in the 1940s. Without being filtered through orchestration, the emotion in Wilson's playing is stronger but, as always, without sentimentality. Of the fourteen tracks on the album, seven are substantial conversations between the two pianists. McPartland and Wilson discuss the difficulties in their early learning of jazz and how they often relied on studying recordings to augment their practice routines. They talk about human engineering in playing, improvisation and the mental process of preparing to play live. Wilson talks about how he addressed related questions while teaching at Julliard and he and McPartland bounce theories off each other.

The seven tracks of music are all standards given warm treatments. Together, Wilson and McPartland emphasize blazing four-handed swing on "I'll Remember April" and "Flying Home." Wilson's take on "Sophisticated Lady" and "Don't Get Around Much Anymore" are less of a nostalgic exercise as he imposes his own determination to add some new life to these over-recorded pieces.

Pianist and composer Peter Madsen established his recording career with two excellent solo albums on the Playscape label. Sphere Essence: Another Side of Monk (2003) has him reworking

Pianist and composer Peter Madsen established his recording career with two excellent solo albums on the Playscape label. Sphere Essence: Another Side of Monk (2003) has him reworking

Thelonious Monk

piano1917 - 1982

The Litchfield Suite, recorded live at the Litchfield Jazz Festival and Camp reflects both the artist's comfort across styles and his personal affinity for the camp where he had taught for a number of years. Along with bassist

Andy McKee

guitarb.1953

Gerald Cleaver

drumsb.1963

McKee's role is often nuanced but with clear distinctions for setting the mood. Cleaver is a fiery accomplice, shifting the direction of the music with daring and multifaceted strokes. The two are perfect compliments to Madsen, a difficult task in that the pianist plays with a fullness that requires little support.

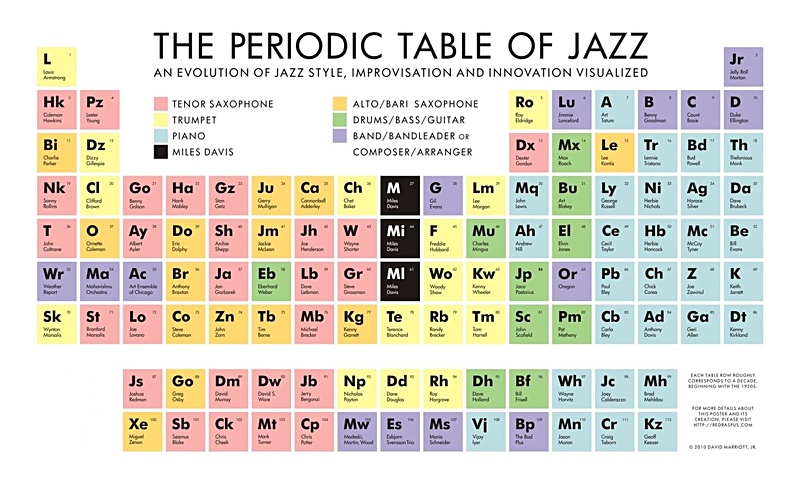

Photo Credit: Periodic Table of Jazz by David Marriott, Jr. (2010)

Tags

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Buy Now

Buy Now