Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » John Riley: Inspiring Innovation

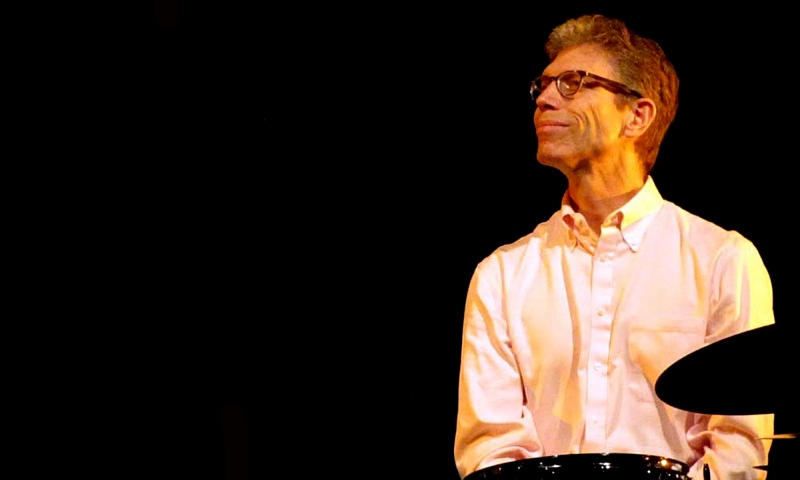

John Riley: Inspiring Innovation

"We're all drawn to the big moments in music; as one listens to something longer and longer, the significance of what a musician is doing most of the time - between the highlights - starts to sink in. That's where one learns about musical balance."

—John Riley

John Riley

drumsb.1954

Miles Davis

trumpet1926 - 1991

Quincy Jones

arranger1933 - 2024

Vanguard Jazz Orchestra

band / ensemble / orchestraAll About Jazz: I've been a fan of yours since I first saw the Live 3 Ways video with

John Scofield

guitarb.1951

Bob Mintzer

saxophoneb.1953

John Riley: We all want to be inspired—and the people that are playing things that seem new or significant to me are the ones that inspire me the most. So, that's what I mean in that case. This is a fluid, evolving endeavor, and I'm always looking at new trends and how they relate to what happened in the past. Just trying to stay inspired and growing through that process.

AAJ: In a lesson a while back, you touched on the concept of wearing different hats. I think this was in the context of my side work as a producer and manager for record labels. In addition to performing as a leader and a sideman you are also a prolific writer and an educator. What moved you to pursue these other vocations and are there other hats you wear that you'd like to share with us?

JR: Well, I started teaching at North Texas my junior year when the school had an overflow of drum students. Currently I'm teaching at Manhattan School of Music and SUNY Purchase in New York and I find the process of teaching to be inspiring in many of the same ways that performing inspires me. I was motivated to publish my books by a drummer named Dan Thress. Dan had been taking lessons from me over the course of a couple of years, and at one point Dan said to me, "I really like these lessons, I don't think there's anything like it on the market, why don't you think about putting a book together?" So he encouraged me to do it and had access to a publisher. That's how the books began.

AAJ: You're well known in the straight-ahead bebop world of drumming. Are there any recordings of you performing avant-garde or fusion styles?

JR: I guess the two most recent recordings I did with trombonist

Luis Bonilla

trombone

Kenny Werner

pianob.1951

Frank Zappa

guitar, electric1940 - 1993

AAJ: Some people might not know this, but you had a chance to play with

Miles Davis

trumpet1926 - 1991

JR: The circumstance of that was kind of unusual. We performed together at Montreux Jazz festival in Switzerland, and

Quincy Jones

arranger1933 - 2024

So, finally Quincy convinced Miles to do this, and I think it was in 1990 or 91. This being in Switzerland, they hired a Swiss pianist named

George Gruntz

piano1932 - 2013

Which, was kind of a crazy idea.

Gil Evans

composer / conductor1912 - 1988

Kenwood Dennard

drumsNow, we get to Montreux and we had 3-4 days of rehearsal. Right off the bat, I see

Grady Tate

drums1932 - 2017

That's the long and the short of the story. It was a fantastic experience. We rehearsed for a couple of days, but Miles didn't show up for the rehearsals. We were rehearsing in the hotel in Switzerland. We knew he was in the hotel, but he never came to the rehearsals until the conclusion of the rehearsal the night before the concert.

At about 10 o'clock we were wrapping up the rehearsal, and Miles kind of floats into the room in this amazing leather suit and giant sunglasses. There's about 40 musicians there, and film crews, and fans and stuff, and Miles walks straight through the crowd of people, right past Quincy Jones, and walks straight up to Grady Tate, and gives him a big bear hug and says, "Man, Klook (

Kenny Clarke

drums1914 - 1985

We rehearsed some more since Miles was there. We rehearsed the next day, and he was in really good spirits, was very playful, and really seemed to be enjoying himself. I think he passed away about 3 or 4 months later. So he must have had some inkling that if he was ever going to do this retrospective, it had to be now.

AAJ: That's a great story.

JR: My role as a musician was kind of minor, but my gratitude for being part of the whole thing is major.

AAJ: I had no idea, I did not know that Grady was involved with that concert.

JR: I think the CD lists Grady and I as the drummers and Kenwood on percussion, but Grady played drums on the whole thing. And Grady actually said, "You should be playing this." But I said "Quincy wants you and that's the way it should be..."

AAJ: All of your books contain chapters where you stress the importance of listening to the music and studying the master drummers. People listen to music differently now than they did even 10 years ago. In your opinion, how has the popularity of streaming radio and Mp3s changed the way young drummers internalize music?

JR: Well, people are bombarded with every possible kind of music, with the entire history of music available to them every second of every day. That's different from 10 years ago or 40 years ago when I would go to a record store and pick up a record. For example, maybe that particular album was a record. I remember this

Chick Corea

piano1941 - 2021

Steve Gadd

drumsb.1945

Chick Corea

piano1941 - 2021

Steve Gadd

drumsb.1945

I had the same experience with many records. Records with

Jack DeJohnette

drumsb.1942

Nowadays that scenario has completely changed. New records are coming out every day, AND even though the entire history of music is available, it seems like people don't know the recordings. Well, let me put it this way. It's rare to find someone who's lived with the recording as long as we used to in the old days.

Music seems to gloss over people just because they don't have to commit to listening to one record. They have opportunities to hear so many. It's almost like having a box of chocolates in front of you. You pick one up and you take a bite out of it and you say "oh yeah, I like that," but you put half of it back in and you pick up another flavor and you say "oh yeah, that's nice too" and you pick up another one and there's a cherry in that and you take a bite out of it, and another one has a nut in it, and then by the fifth one you don't taste anything any more.

When you have that one recording called Four and More or that one recording called Speak No Evil, and you listen to that record every day for months and you know every part that every musician on the recording plays and can sing them all, there's a kind of a depth that appears. You can't achieve this when you listen to something once, or you listen to ONE song from Speak No Evil. I think that it's unfortunate that glossing over stuff seems to be the trend. In my opinion, everything is out there tempting you to listen to it. The people that I admire all seem to have spent a lot of time listening to particular recordings, and really absorbing the material.

AAJ: Do you feel with the way that vinyl is coming back into vogue, that on some level that aspect of digesting an album might be coming back?

JR: Well it's possible but I'm not hopeful. Having the stuff on your iPhone is so much easier, it's unfortunate. Well, it's fortunate that everything's available because I'm hearing things I've never heard before. But it's unfortunate that musicians at an earlier developmental stage are more inclined to get at the surface of many things as opposed to the depth of a few things.

AAJ: I have to say I agree with everything you just said, especially concerning the disposability of music nowadays. From a quantitative point of view, the money that would have come in from album sales or even song downloads has kind of dissipated. What would have been one dollar or ten dollars, is now a penny or ten pennies for a song that's been streamed, and it doesn't seem like people are listening to things more than 2 or 3 times before they move on to something else.

JR: Yeah, that seems to be the way it is, yet that's not the way the people who made those early records listened to music. I remember

Jimmy Heath

saxophone, tenor1926 - 2020

Jay McShann

piano1909 - 2006

Charlie Parker

saxophone, alto1920 - 1955

Charlie Parker

saxophone, alto1920 - 1955

AAJ: I guess I could say, I concur. I don't really have an answer—I guess that's just the way things are now.

JR: That's the way things have evolved. There are a lot of virtuoso players today, so I guess this new way of looking at things isn't affecting their craftsmanship, but it may be affecting the way they're using their craft.

AAJ: Do you think people are just spending a lot of time in practice rooms and not sitting down and focusing and listening to music?

JR: I think people are spending a lot of time in practice rooms, and becoming fantastic athletes on the instrument, and that dimension can influence how one approaches the music. To follow up on what we discussed earlier: when one listens to tons of music rather than live with a smaller collection of music what seems to stick with you are the "highlights" or busiest moments for all those recordings. Of course we're all drawn to the big moments in the music; I've found that as one listens to something longer and longer, the significance of what a musician is doing most of the time—between those highlights—starts to sink in and that's where one learns about musical balance, to be patient and musically supportive.

AAJ: Before we finish, I had one more kind of "fun" question to wrap this up. Living in New York, one of the things that surprised me was the fact that most drummers seem to use the same 4 piece set up that you use. Visiting drummers seem to pare down their kits as soon as they reach the city limits. Is it really too much to ask for one extra tom?

JR: Well, when I first moved to New York I would carry my drum set on the subway. So I had to carry everything and get it up and down the stairs in one trip, otherwise I would carry one half the kit down and when I would get back up the stairs to get the other half, it would be gone. A lot of people get accustomed to carrying small kits because they're schlepping the stuff around. Now things are changed so many of the clubs have their own drum sets. They got tired of having drummers carrying stuff in and out and bumping into tables and customers, so that was the choice of the clubs or the budgets of the clubs that limited them to those 4 piece kits. I'm fortunate to play at the Village Vanguard which is one of the last clubs in New York where people play their own instruments. When

Tony Williams

drums1945 - 1997

AAJ: I didn't know that the Vanguard didn't have a back line, well I guess I've only ever seen you play there.

JR: Well my drums are there because I'm there every week [with the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra}. But they're only played on Mondays. When

Al Foster

drums1944 - 2025

Lewis Nash

drumsb.1958

Tags

John Riley

Interview

Ben Scholz

United States

Illinois

Chicago

Miles Davis

Quincy Jones

Vanguard Jazz Orchestra

John Scofield

bob mintzer

New York

Luis Bonilla

Kenny Werner

Frank Zappa

montreux jazz festival

Switzerland

George Gruntz

Gil Evans

Kenwood Dennard

Grady Tate

Kenny Clarke

Chick Corea

Steve Gadd

Jack DeJohnette

Jimmy Heath

Jay McShann

Charlie Parker

Village Vanguard

Tony Williams

Blue Note

Al Foster

Lewis Nash

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Go Ad Free!

To maintain our platform while developing new means to foster jazz discovery and connectivity, we need your help. You can become a sustaining member for as little as $20 and in return, we'll immediately hide those pesky ads plus provide access to future articles for a full year. This winning combination vastly improves your AAJ experience and allow us to vigorously build on the pioneering work we first started in 1995. So enjoy an ad-free AAJ experience and help us remain a positive beacon for jazz by making a donation today.

Chicago

Concert Guide | Venue Guide | Local Businesses

| More...

Buy Now

Buy Now