Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Alan Broadbent: Intimate Reflections on a Passion for Jazz

Alan Broadbent: Intimate Reflections on a Passion for Jazz

The purpose of my performing is to communicate things that touch others emotionally, and sometimes it might become a work of art.

—Alan Broadbent

Dave Brubeck

piano1920 - 2012

Lennie Tristano

piano1919 - 1978

Natalie Cole

vocals1950 - 2015

Diana Krall

piano and vocalsb.1964

In this interview, he emphasizes that he sees jazz as an art form and takes virtually every note to heart, seeking to express something that captures the essence of musical expression. From Tristano, he learned the importance of jazz timing and rhythm. Broadbent sees rhythm as the most important quality that a musician can express on his instrument. He also has an abiding interest in classical music, especially Gustav Mahler's symphonies, which has strongly influenced his work.

Broadbent is a serious thinker, but not without a sly sense of humor. He is also a good story teller. In this two part interview, he weaves between stories of himself and his cohorts and insights into music and life. He seems to be gripped by jazz, as if it is what gives meaning and significance to his existence -and he pulls no punches in saying that any musician who doesn't feel that is missing the mark. All About Jazz contributor Vic Schermer gave him twice the time he usually reserves for interviews because he felt that Broadbent has something very important to say that can't be said quickly. Here, Broadbent generously and authentically provides an intimate look at a musician and his work. The first part of this interview concludes around the time he worked with Natalie Cole in the 1990s. The second part brings us up to the present. Both are filled with fresh insights about the music and the musician.

PART I: COMING UP AND BRANCHING OUT

All About Jazz: Let me start out by asking you the desert island question. Which recordings would you take to that desert island if they were the only ones you could listen to?Alan Broadbent: I would definitely take the

Charlie Parker

saxophone, alto1920 - 1955

Another album would be The Amazing Bud Powell, Vols. 1 and 2 (Blue Note, 1952, 1956). And then I would bring along recordings of the music all the symphonies of the one and only classical composer Gustav Mahler. He was composing and conducting at the turn of the century when in Vienna and Paris, with Ravel, Debussy and Stravinsky, there was that flowering of musical discovery. I would take all of Mahler's symphonies. I would take the scores rather than recordings because I can hear them just by reading the notes. I live in a world of orchestral music. I would take things with me that I can learn from, where listening is also a learning experience. So I've gotten got the desert island list down to Bird, Lennie, Bud, and Gustav Mahler!

AAJ: Would you say you're still learning from Bird and Bud?

AB: Oh, yes. But it's not as if learning to me means copying down the a solo and analyzing it. No, it's immediate, as if Bird is speaking to me and saying, "I've got something that you need to hear."

Coming of Age in New Zealand

AAJ: To go back to your childhood, you grew up in Auckland, New Zealand. What were your earliest exposures to music there?AB: When I was six, I studied piano with the nuns in the Catholic school I attended. They didn't have a lot to do with my musical development, but I practiced dutifully and learned the scales and so on. Then, when I was around twelve, I found myself dissatisfied with what I was being taught. I wanted to compose, and I knew I wanted to be a musician, but I also knew I would never master difficult pieces like the Chopin Etudes because, although I loved the music, I didn't have that kind of discipline. I could never be like the great concert pianist Yuja Wang, for example. I love the way she plays. She is an interpreter who transcends the written note to reveal the soul of the composer. She is one of the living greats of our century, and I'm glad to be alive to experience her transcendence. But, for myself, I also knew I wanted to be more of a musician than a pianist.

My dad had a lot of the sheet music, which I would sight read and select the ones I liked best. New Zealand was a very backwoods parochial country at that time. It was isolated from everywhere, including Australia. We had little more than the BBC radio programs. I had no at home access to orchestral music, so I went to the library, and I discovered some things I loved. Then at thirteen, I remember discovering some scores, like a string quartet by Benjamin Britten, which I studied, even though I couldn't get a recording of it.

So I had that kind of developing interest in music and the ability to read scores. I was a pretty good sight reader, playing all those standard tunes I listened to on my dad's phonograph, and I would pick out the ones that were most musical to me, that had something a little different that appealed to me. For example, I've always been moved by musical intervals. When most people in pop culture talk about music today, they equate it with the words of a song, and they'll sing the lyrics for to you. But what about the music itself? Much of it is pretty jejune. So, I would play through these tunes and make my own little arrangements of tunes like

Paul Whiteman

composer / conductor1890 - 1967

In addition, my friend's brother was a bassoonist in the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, and he became my personal contact with the music world. Around that time in 1961, I heard Dave Brubeck on the radio doing

Paul Desmond

saxophone, alto1924 - 1977

Dave came out and sat confidently at the piano. Paul positioned himself on the curve of the piano, and they played "Tangerine." I already knew it from my dad's collection, and the intervals appealed to me, especially when it went to A major. I thought that was beautiful. And I found I understood the harmonies completely. And then I heard Paul Desmond playing as if he were singing. I never knew you could do that with an instrument. I dug the way Desmond played, and Dave's comping. But there was this other thing going on with me. Besides my mind and heart being moved by the sound, there was this feeling, this pulse. Even with Dave Brubeck and his thumping away, there was this pulse that I couldn't get out of my body. The jazz rhythm brought my intellect and feelings up on an equal level in a way I had never experienced before.

So, very excited, I went and found the transcriptions that Dave Brubeck's brother Howard transcribed from Dave's solo album called Brubeck Plays Brubeck (Columbia, 1956). I couldn't get the record, but I started sight-reading the transcriptions, and it was like every chord, every progression was a miracle to me. I soaked it up, and I loved every minute of the time that I spent with that music. But the thing that I had to get right when I played it was the rhythmic feeling, and that came very hard. As I'll explain, I finally got it right after working at it on my first gigs.

Shortly after the Brubeck transcriptions, I saw an ad in the paper that some guys were forming a jazz group, and they wanted a pianist. So I sat in -it was the first time I ever played with a bassist and drummer, and it was a lot of fun. Then, when I was about sixteen or so, I got a serious call from the "big boys." We have two famous down under jazz pianists: one is Mike Nock and the other is the phenomenal Dave MacRae. Dave had played with

Buddy Rich

drums1917 - 1987

Michael White

b.1954When we played clubs, Tony would get all pissed off because frankly my time was un-swinging, and he would get all frustrated, like, "This kid was supposed to be a whiz!" Finally, he told me to go home and start listening to

Wynton Kelly

piano1931 - 1971

Red Garland

piano1923 - 1984

From there, I began listening to

Bud Powell

piano1924 - 1966

AAJ: You haven't mentioned any horn players so far other than Desmond. When did they take on importance for you?

AB: I did play with a couple of horn players in New Zealand, but more importantly, I was listening to recordings. I guess it was Charlie Parker, of course, who I'd listen to over and over. And then I found

Lee Konitz

saxophone, alto1927 - 2020

Don Falzone

bass

Louis Armstrong

trumpet and vocals1901 - 1971

AAJ: Parenthetically, I wanted to ask whether you were exposed to any Maori music in New Zealand.

AB: Very little. I listened to some Polynesian, and Maori music on the radio, but most of it has westernized harmonies and I don't feel any connection to it. It belongs to their own cultures. I grew up in a very white Christian Protestant environment. I had a couple of Maori friends, but I later lost contact with them. The 1950s in New Zealand was quite backward, still a lot like it was in the late 1800s. Even Mark Twain would back me up on that. When he visited New Zealand in the late 1800s, it was even further back in time. When I was growing up there, there was no free trade. TV was in its infancy even in the 1960s there. There were no new cars -you had to buy a used car, the technology was backward, and it was a very prudish society. Playboy magazine was banned. The wonderful British actress Diana Dors came to New Zealand and was railed upon because of her supposed promiscuity. I remember an uproar over a visit by the great

Eartha Kitt

vocals1927 - 2008

Berklee and Lennie Tristano: The Weekly Commute

AAJ: By contrast with what you grew up with, the jazz world is very earthy and very multicultural. How did you come to make that huge leap half way around the world to Berklee and a whole new life?AB: The jazz I know is an art form. And that's what I as a boy of age fourteen got interested in. Pursuing that art form was what got me to the famous Berklee College of Music in the 1960s. When I was eighteen, I received the Downbeat scholarship to go to Berklee in Boston. There, I was able to really develop my skills more seriously. For one thing, Boston unlike Auckland, had a lively jazz and classical music scene. Right away, I got a student ticket to go to the Boston Symphony concerts. I heard Ravel and Stravinsky for the first time live. I saw

Leonard Bernstein

composer / conductor1918 - 1990

Miles Davis

trumpet1926 - 1991

Bill Evans

piano1929 - 1980

Lee Konitz

saxophone, alto1927 - 2020

AAJ: At the school itself, with whom did you study?

AB: My arranging teacher was

Herb Pomeroy

trumpet1930 - 2007

AAJ: Many of the best composers/arrangers, like

Bob Brookmeyer

trombone1929 - 2011

Maria Schneider

composer / conductorAB: I also studied with

Ray Santisi

piano1933 - 2014

AAJ: You studied with Lennie already while you were still a student at Berklee?

AB: At my first summer break, I made contact with Lennie through a friend. I called him, and at first he turned me down, but my friend said, "Keep at it. Call him again." After a couple of calls, he agreed to teach me. So every week I'd take a plane from Boston to LaGuardia Airport and study with Lennie. It was in 1967-68, and he was living not far from the airport at the time in Flushing, Queens.

AAJ: Did you take formal lessons, or was it more like mentoring?

AB: It was a personal connection. I was sort of a lonely kid, and he was a father figure to me. Musically, I could swing. My technique was somewhat lacking, as it still is, but Lennie refined my ability to play what I hear. For example, he would have me transcribe

Lester Young

saxophone1909 - 1959

Count Basie

piano1904 - 1984

AAJ: Wouldn't the pitch change if you played it at half speed on the record player?

AB: It would be an octave lower. Lennie felt that even at half speed, Lester's intensity remained the same. The same was true of Bud Powell: the intensity and engagement with the time was there even at half speed. This is an important point. If you listen to some other pianists at half speed, you can hear that the music isn't embedded in the time the way it is with Lester and Bud. Bob Brookmeyer said that if you can't "feel" the time, you can't get membership in that special club of those who can. It's a very special ability. And we musicians all know when we play together that that feeling is of paramount importance, because if one of us is not engaged in the time, then it all just goes to hell. But if the group of us are all embedded in that feeling of time, then we can communicate it to our listeners. I could make a comparison to a sailboat, where to catch the wind, everyone in the boat has to lean the same way to the sides. If someone isn't leaning, we're screwed!

AAJ: Listening to a group, you can feel them leaning the right way into the time. It's hard to explain, but it really has to happen for the music to be great. And some musicians can never get that, like some classical players can never swing.

AB: Even Leonard Bernstein didn't quite get that feeling. [Broadbent sings the "Jets" song from West Side Story, mocking the halting rhythm.] I have all his show scores, and they're great, but his jazz writing, even his virtuosic "Prelude, Fugue and Riffs," is just an imitation of the rhythm and not the thing itself. They don't quite have the jazz rhythm.

AAJ: I thought that Bernstein really picked up on the jazz idiom.

AB: No. Well, he got the notes and the phrasing of jazz. But the "time" is different. It's that special feeling of flow that only some musicians can get. Bernstein got as far as Dixieland music with that part.

AAJ: So, Tristano really instilled that flow, that special feeling in you, by having you sing back solos that exemplified it.

AB: Tristano taught the two things that

Oscar Peterson

piano1925 - 2007

Coleman Hawkins

saxophone, tenor1904 - 1969

AAJ: Getting back to Berklee, did you play gigs while you were there?

AB: All the time. I played at the Hotel Vendome, which later burned down.

AAJ: Your bio isn't clear what you did right after you finished Berklee. What happened next?

Woody 'N You

AB: After Berklee, I needed a gig. At the time, Jake Hannah and

Nat Pierce

piano1925 - 1992

Anyway, being on the road was stressful. I did three years with the band. At one point, we did eighty one-nighters in a row—imagine eighty one-nighters on a bus, "ghosting" (doubling up, to save money) in hotels, sleeping on the bus with bottles of Nyquil and three pillows, feeling every pothole bump of the bus. It was a personal hell for me, and I just sort of fell off the bus in Los Angeles and settled in there. I didn't work too much at first. I couldn't bring myself to make phone calls, I was shy about socializing, and I was going through personal problems. I was living in a crummy little apartment and then when one day I got a phone call from a wonderful guy named " data-original-title="" title="">Tommy Shepard. He asked me if I had a tux or a dark suit (I had a sort of dark suit), and said to come down to the Sheraton Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard. "We start at eight o'clock" I said, "O.K."

Nelson Riddle

I go there, and as I'm walking to the stage, I see it's for a big dance band, and there are all these older guys. I sit down at the piano, and as I'm looking at the music, I see

Nelson Riddle

arranger1921 - 1985

Alvin Stoller

drumsb.1925

Nelson liked players who could sight read well and had that correct feeling with the time that I spoke about earlier. He felt I could do that well, so he got me to do some of his TV shows (this was long after his work with Sinatra). I came to the studio at 8 am. I had no idea what to do, so I asked Willy Schwartz, "What am I supposed to do?" He said, "When you hear the click, count to eight and play!" [Laughter!] But it all worked, I figured out how to do it. What Nelson particularly liked to do after the session was to have the rhythm section play some "source music," original tunes he wanted to use for some purpose, say, the guy in the TV show turns on the radio in his car as he hurtles down the Pacific Coast Highway. So there I am swinging away with Nelson sitting beside me. "Okay," he'd say, "Let's try this one." Precious memory. So for a while I worked in the L.A. studio scene, but then synthesizers came along, and I hated them. To me, synthesizers are built to replicate sounds, not feelings, and I never could get anything out of them that I felt about the music.

Working With Singers: Irene Kral, Natalie Cole, Others

AAJ: Did you work in clubs at all?AB: At that time, there was only one club of any note in L.A.: Dontes.' That's where I met

Irene Kral

vocals1932 - 1978

AAJ: The first exposure I had to your playing was her album, Irene Kral Live (Just Jazz, 2000, recorded 1977). I was really impressed by your comping for her, which supported her singing more than most pianists would. That stayed with me for years. Then a few months ago, I was poking around the web, and found out that in the intervening time, you became famous, one of the top pianists around! But your playing on that album really stuck with me for years.

AB: To your point about me being famous, "famous jazz musician" is an oxymoron, really. Just ask anybody on the street what they think of Oscar Peterson and I guarantee you'll get puzzled looks. And I'm not even close to his or

Herbie Hancock

pianob.1940

Roy Kral

b.1921I also worked back then with

Sue Raney

vocalsb.1940

Carmen McRae

vocals1920 - 1994

Jimmy Rowles

piano1918 - 1996

Clare Fischer

piano1928 - 2012

Nat King Cole

piano and vocals1919 - 1965

That worked out well, and after that, I started touring with them. While doing that stint as pianist, I studied all the scores the band had of

Johnny Mandel

arrangerb.1925

Marty Paich

composer / conductor1925 - 1995

Michel Legrand

piano1932 - 2019

Then Natalie told me she was going to do a second album, and she casually asked me on the bus if I would arrange the tune "Crazy He Calls Me" for her. I of course knew it from

Billie Holiday

vocals1915 - 1959

Charlie Haden Quartet West

AB: Soon after that tour, I got a call that totally surprised me. A guy called and said, "Hey man, I heard your music on the radio. I came home, and I called the station to ask who it was. It sounded beautiful, man. I just moved to L.A. and I'm trying to form a group here. I'm gonna call the group "Quartet West." It was

Charlie Haden

bass, acoustic1937 - 2014

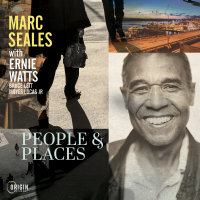

Ernie Watts

saxophone, tenorb.1945

Larance Marable

drums1929 - 2012

AAJ: I think of Charlie Haden in connection with his "free jazz" period with

Ornette Coleman

saxophone, alto1930 - 2015

AB: What people don't realize is that Charlie was the foundation of that group with Ornette. He was the rock; he held it all together. Haden had phenomenal ears. But apart from his time with Ornette, he was a relatively conservative musician. He grew up with bluegrass. His family members were all radio stars in the Midwest. So he had that bluegrass tradition in him. He actually didn't like it when I played too far out! However, it usually worked well between us because we found a niche with what came to be called film noir jazz or something like that. So we did well together. I composed pieces for the group, and we began touring all over.

Pushing the Edge of The Mainstream

AAJ: When you play, much of the time, you are very careful and disciplined in staying within traditional harmonies, but at times you stretch the limits. Your recording of Ornette's "Lonely Woman" in your solo piano album Heart to Heart (Chilly Bin, 2013) is groundbreaking. Doing standards, you sometimes insert less traditional harmonies. So I wonder what your feelings are about avant-garde music and the remarkably expanded variety of genres and styles that jazz players are doing today?AB: Yes, jazz is very much expanding. For me, however, what I play is determined by what I'm doing at the moment. There's no contrivance; it just comes out at the moment. I'm not trying to be conservative or avant-garde or whatever. If I do go out beyond the expected harmonies, it's not contrived. It's just what I feel at the moment. All those different definitions and genres of jazz mean nothing to me. I just follow

Duke Ellington

piano1899 - 1974

A Love of Mahler and Classical Music

AB: In my free time, when I just listen to music, I listen not so much to jazz but to symphonies, Mozart, Elliot Carter, John Adams. I love Schoenberg, Ravel. But it was on one of those Nelson Riddle Universal Studio TV dates when I'd be driving there in my car early in the morning, I'd have the classical music station on, and I'd pull into the Universal parking lot, and then I heard Gustav Mahler's First Symphony, "The Titan," for the first time. It was music that all my life I wished I had written. This would have been 1978 or so, just after Irene died. Mahler was speaking to me through his music. From that moment on, I've spent years studying Mahler, and I have all the scores and a lot of facsimiles of his music. And Leonard Bernstein came along with his video recordings of Mahler which had a big impact on me. I already had all of those, along with my Stravinsky scores, my Debussy, Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, I have them all. I love Webern and Alban Berg; to me they're like Mahler distilled.With Mahler I could open a random page to anyone of his scores, pick out a phrase, and I go "When you do this [in the score], you get that [sound]!" Especially with Mahler, the connection between his feelings, the notes, and the sound that he chose for those notes, create that deep, artistic epiphany that's the same as what Bud Powell does to me when he plays. It's the same thing: the truth. Not Bud Powell's truth or Mahler's truth. It's the truth of the art, the humanity of it.

PART II: A LIFE OF IMMERSION IN MUSIC

The Fine Art of Jazz Rhythm

AAJ: Let's try to bring your career up to date. When I reviewed your sets at the Deer Head Inn, you said something that really struck me as a very powerful statement about your goals as a musician. You said, "The purpose of my performing is to communicate things that touch others emotionally, and sometimes it might become a work of art." I'd like to know what that means to you personally. And what comes to your mind about music from the history of jazz that fulfill those goals and which for you are examples of jazz as works of art?AB: For me it's when the emotional aspect of music -the capacity to communicate through notes what you can't express verbally -and the intellectual aspect -your musical knowledge (what you know verbally)—become like one. It's the opposite of what Nelson Riddle called the "no, no pianists." They play a chord, and they move their head back and forth from left to right as if they're saying "no." [Laughter.] They bang out notes without a purpose. That's not my thing. I want to think and feel something important when I play.

Bud Powell used to insist on a seriousness of purpose. There are magnificent examples of such purpose in the history of jazz. Like the Tristano album, Lineup (Atlantic, 1955). And his "Requiem" (Lennie Tristano: Requiem, Atlantic, 1980, recorded 1955), which he composed and improvised after

Dizzy Gillespie

trumpet1917 - 1993

What makes these compositions and performances art is the immediacy of it. Early

Bill Evans

piano1929 - 1980

Another way to understand the artistic difference that I'm talking about can be heard say, if you compare the singers

Billie Holiday

vocals1915 - 1959

Lena Horne

vocals1917 - 2010

Louis Armstrong

trumpet and vocals1901 - 1971

Anita O'Day

vocals1919 - 2006

Tags

Interviews

Victor L. Schermer

Dave Brubeck

Lennie Tristano

Natalie Cole

Diana Krall

Charlie Parker

Paul Whiteman

Paul Desmond

Mike Nock

Dave MacRae

Buddy Rich

Michael White

Tony Hopkins

Wynton Kelly

Red Garland

Bud Powell

Lee Konitz

Don Falzone

Louis Armstrong

Eartha Kitt

Leonard Bernstein conduct

Miles Davis

Bill Evans

Cannonball Adderley

Herb Pomeroy

Bob Brookmeyer

Maria Schneider

Ray Santisi

Lester Young

Count Basie

oscar peterson

Coleman Hawkins

Jake Hannah

Nat Pierce

Tommy Shepard

Nelson Riddle

Willie Schwartz

Harry Klee

Alvin Stoller

Irene Kral

Herbie Hancock

Roy Kral

Sue Raney

Carmen McRae

Jimmy Rowles

Natalie Cole

Clare Fischer

Nat "King" Cole

Johnny Mandel

Marty Paich

Michel Legrand

Billie Holiday

Charlie Haden

ernie watts

Larance Marable

Ornette Coleman

duke ellington

Dizzy Gillespie

Billie Holiday

Lena Horne

Anita O'Day

Sheila Jordan

Jackie Byard

Harvie S

Dave Liebman

Hank Jones

Keith Jarrett

Chick Corea

Tommy Flanagan

Tony Bennett

Billy Mintz

Paul McCartney

Tommy LiPuma

Steve Tyrell

Kristen Chenoweth

Ralph Kemper

Andre Previn

A Touch of Elegance: The Music of Duke Ellington

Red Mitchell

Frank Kapp

Rolling Stones

Sonny Rollins

Max Roach

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Alan Broadbent Concerts

Sep

20

Sat

Piano Jazz Series: Alan Broadbent

KlavierhausNew York, NY

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

Buy Now

Buy Now